Poems for Advanced Children and Beginning Parents

by John Ciardi

illustrated by Becky Gaver

Houghton Mifflin 1975

A somewhat lackluster collection of poems for children by an otherwise great American poet who might have been caught in the trade winds of children's poetry...

I have read various collections of Ciardi's poems over the years and find him to be rather sturdy when it comes to quality, though I have to confess I have yet to come across a poem of his I wanted to quote or memorize. Whether or not this should be a measure of a good or great poet can be debated, but I would argue that with poetry, with so much focused on the language and the phrasing, the idea of being moved by a particular passage or insight is crucial.

In reading this collection I had a strange feeling of displacement. Not of myself but of the poems and the poet. This collection came out a full year after Shel Silverstein's Where the Sidewalk Ends, a book whose poems still resonate today, and between these two titles I get the feeling there was a seismic shift in poetry for children.

Ciardi was of the old school, a more pastoral observer. He writes poems about the differences between youth and age (the title poem), meditations on nature ("Why the Sky is Blue"), and the nature of friendship ("What Johnny Told Me"). Some of the poems are short but many are lengthy narratives that seem more keen on telling a quirky story in rhyme as if somehow the beat and the meter will transcend the absurdities of the narrative ("A Fog Full of Apes"). On the other hand you have Silverstien's odd paeans to selling one's sibling ("For Sale"), advice on avoiding those who would stiffle your dreams ("Listen to the Mustn'ts") and the cautionary tales of children who refuse to do chores ("Sarah Cynthia Sylvia Stout..."). Silverstien's poems often read like short jokes and one-liners, but as subject matter they celebrate the world of the child from the child's perspective; Ciardi's poems come from a top-down world view.

Perhaps it's unfair to compare these two, but while reading Fast & Slow I couldn't help feel that sense that I was witnessing the historical shift in children's poetry between the old and the new. Scholars can probably define it better, for me reading Ciardi felt for the first time like I was listening to a kindergarten teacher on the edge of retirement treating her charges the same way she did forty years earlier. There's a stodgy innocence in these poems; they aren't bad, necessarily, but neither are they bold, adventurous, or relevant. There is a reason Where the Sidewalk Ends keeps getting anniversary editions and Ciardi's books keep turning up in the withdrawn and discard bis at the library. It's sad to think of poetry falling out of favor, and to have it replaced with works that are newer and flashier and perhaps weaker in their poetic rigor, but I totally understand.

Monday, August 23

Friday, August 20

The Adventures of Ook and Gluk

Kung-Fu Cavemen From the Future

The second graphic novel by

George Beard and Harold Hutchins

the creators of

Captain Underpants

(along with Dav Pilkey)

Blue Sky Press / Scholastic 2010

Those bad boys of hypnotic mischief are back (finally!) with an epic 175 page tale of time-traveling cavemen who learn kung-fu and save the planet, both then and in the future. Really, do you need to know anything more?

While many have looked forward to the third book in another series this summer -- something about games of hunger, or something -- this is the book I've been looking forward to. And for no other reason that it's about dang time Dav Pilkey put out another book. What's it been, four or five years now? Imagine if you FOK-ers (Friends of Katniss, what did you think I meant?) had to wait four years for another installment instead of a single year.

So Ook and Gluk. They're cavemen. They get into mischief just like their creators, George and Harold, the two boys who created Captain Underpants, who is in fact their school principal under hypnosis. Never mind that story, it doesn't come into play here. Instead we have a couple of cave boys who run afoul a dude that looks like a cross between a tiki god and a salt shaker named Big Chief Goppernopper. One thing leads to another, Goppernopper has his goons out to destroy the boys, and so on and son on, until one day Goppernopper comes across some guys in heavy machinery clearing whole forests. Turns out that a Gopernopper of the future has depleted the planet's resources hundreds of thousands of years in the future and has come back through time to steal the resources available from the past. Bada boom, bada bing, the boys are fugitives and wind up stuck in the future until they can think up a way to go back and save the past. Luck has them hook up with a kung-fu master who teaches them the martial arts and how to not use violence to solve their problems...

Look, naturally everything turns out okay in the end. This isn't a ride you get on for the scenery, or the flowery language (though sensei Wong gives the boys a bit of wax-on wax-off style philosophy), this is a book you gobble up for fun, and then start over from the beginning because there isn't anything else to read. Not like this. This is the long-form graphic novel that third grade (and some WAY older) boys have been waiting for, and it comes as a perfect late-summer respite to required summer reading.

Granted, we are talking about the type of antics seen in countless cartoons on television, the one-dimensional bad guys, the simple chase scenes, but how different is this really from any other genre reading out there? It's got drawings, and puns, misspelled words and crazy flip-o-rama animation at the end of every chapter. It's got cavemen and robots and time machines and kung-fu. It's got boys behaving like boys and, believe it or not, a bit of romance and puberty thrown in for good measure. Sure, there's a problem with the time travel continuum and the messing with events thing, and I'll bet there are still parents and teachers and librarians out there who find these comic adventures inane and loathsome.

So yeah. No ALA medals here. And so what?

The second graphic novel by

George Beard and Harold Hutchins

the creators of

Captain Underpants

(along with Dav Pilkey)

Blue Sky Press / Scholastic 2010

Those bad boys of hypnotic mischief are back (finally!) with an epic 175 page tale of time-traveling cavemen who learn kung-fu and save the planet, both then and in the future. Really, do you need to know anything more?

While many have looked forward to the third book in another series this summer -- something about games of hunger, or something -- this is the book I've been looking forward to. And for no other reason that it's about dang time Dav Pilkey put out another book. What's it been, four or five years now? Imagine if you FOK-ers (Friends of Katniss, what did you think I meant?) had to wait four years for another installment instead of a single year.

So Ook and Gluk. They're cavemen. They get into mischief just like their creators, George and Harold, the two boys who created Captain Underpants, who is in fact their school principal under hypnosis. Never mind that story, it doesn't come into play here. Instead we have a couple of cave boys who run afoul a dude that looks like a cross between a tiki god and a salt shaker named Big Chief Goppernopper. One thing leads to another, Goppernopper has his goons out to destroy the boys, and so on and son on, until one day Goppernopper comes across some guys in heavy machinery clearing whole forests. Turns out that a Gopernopper of the future has depleted the planet's resources hundreds of thousands of years in the future and has come back through time to steal the resources available from the past. Bada boom, bada bing, the boys are fugitives and wind up stuck in the future until they can think up a way to go back and save the past. Luck has them hook up with a kung-fu master who teaches them the martial arts and how to not use violence to solve their problems...

Look, naturally everything turns out okay in the end. This isn't a ride you get on for the scenery, or the flowery language (though sensei Wong gives the boys a bit of wax-on wax-off style philosophy), this is a book you gobble up for fun, and then start over from the beginning because there isn't anything else to read. Not like this. This is the long-form graphic novel that third grade (and some WAY older) boys have been waiting for, and it comes as a perfect late-summer respite to required summer reading.

Granted, we are talking about the type of antics seen in countless cartoons on television, the one-dimensional bad guys, the simple chase scenes, but how different is this really from any other genre reading out there? It's got drawings, and puns, misspelled words and crazy flip-o-rama animation at the end of every chapter. It's got cavemen and robots and time machines and kung-fu. It's got boys behaving like boys and, believe it or not, a bit of romance and puberty thrown in for good measure. Sure, there's a problem with the time travel continuum and the messing with events thing, and I'll bet there are still parents and teachers and librarians out there who find these comic adventures inane and loathsome.

So yeah. No ALA medals here. And so what?

Labels:

captain underpants,

cavemen,

comics,

dav pilkey,

graphic novel,

time travel

Friday, August 13

Calamity Jack

written by Shannon and Dean Hale

illustrated by Nathan Hale

Bloomsbury 2010

Sequel to the graphic novel Rapunzel' Revenge, this time following the backstory and continuing adventures of Jack, skewering fairy tales along the way.

Having helped Rapunzel escape, Jack's intention is to bring her back to his home city of Shyport and make restitution for the mess he's left behind. And what a mess. There's a reason this boy is nicknamed Calamity, and you know it's bad when even your family members wish you away so as to stop harming them in the process.

As this is a world based on fairy tales, we learn that Jack is none other than Beanstalk Jack, with perhaps a bit of Jack-be-nimble thrown in to account for his days as a petty thief. As the tale goes, Jack discovers the Giant in the sky – here, he's a wealthy Baron living in a floating penthouse – wherein an uncooperative golden goose is kept. The Giant also brings his own special flour to be used by Jack's mother in her bakery to make bread. One guess what the Giant grinds to make that flour. Liberating the goose infuriates the Giant but Jack leaves town with a price on his head without thinking about the consequences of his actions.

This is the backstory that leads up to Repunzel's Revenge, and serves as the introduction to Jack's return. Hoping to show off his old town Jack finds much has changed. The town is menaced by massive ants who destroy the town (or at least specifically targeted places in town) only to be driven off by the Giant's army. Shyport looks like a cross between three different London's: steampunk, Dickensian, and WII. And all of this chaos brought on by Jack's misadventure many years previous. Naturally, it's up to Jack (with the help of Rapunzel and some friends from his previous life) to set things right.

Hinted at in the first book, and played up here, there is a romantic element between Jack and Rapunzel. It's never really been a secret to anyone but Jack, including readers, and there's a bit of his bumbling that makes me reach the edge of that place where I want to shout "Oh, just kiss her already!" With their budding romance at the end, and their flying off into the moonrise in a zeppelin chased by the Jabberwocky, it seems as if there will certainly be a third book in this graphic novel series.

As a follow-up to Rapunzel's Revenge this book does a nice job filling Jack's past while bringing both characters forward in a continuation of their adventures together. It does occasionally suffer the problem inherent in many comics of bringing readers up to speed with a sort of "origins story" but with some minor reservations the sequel is as strong as its predecessor.

And on a side note, while a certain series concerning Hunger and Games has been anxiously awaited in this house by a certain teen, this was the book my tween daughter could not wait for me to put into her hands at the beginning of summer vacation. She could not (or would not) explain why she wanted to read it so badly, only that she was willing to even clean her room and do her own laundry in order to read it. For what it's worth.

illustrated by Nathan Hale

Bloomsbury 2010

Sequel to the graphic novel Rapunzel' Revenge, this time following the backstory and continuing adventures of Jack, skewering fairy tales along the way.

Having helped Rapunzel escape, Jack's intention is to bring her back to his home city of Shyport and make restitution for the mess he's left behind. And what a mess. There's a reason this boy is nicknamed Calamity, and you know it's bad when even your family members wish you away so as to stop harming them in the process.

As this is a world based on fairy tales, we learn that Jack is none other than Beanstalk Jack, with perhaps a bit of Jack-be-nimble thrown in to account for his days as a petty thief. As the tale goes, Jack discovers the Giant in the sky – here, he's a wealthy Baron living in a floating penthouse – wherein an uncooperative golden goose is kept. The Giant also brings his own special flour to be used by Jack's mother in her bakery to make bread. One guess what the Giant grinds to make that flour. Liberating the goose infuriates the Giant but Jack leaves town with a price on his head without thinking about the consequences of his actions.

This is the backstory that leads up to Repunzel's Revenge, and serves as the introduction to Jack's return. Hoping to show off his old town Jack finds much has changed. The town is menaced by massive ants who destroy the town (or at least specifically targeted places in town) only to be driven off by the Giant's army. Shyport looks like a cross between three different London's: steampunk, Dickensian, and WII. And all of this chaos brought on by Jack's misadventure many years previous. Naturally, it's up to Jack (with the help of Rapunzel and some friends from his previous life) to set things right.

Hinted at in the first book, and played up here, there is a romantic element between Jack and Rapunzel. It's never really been a secret to anyone but Jack, including readers, and there's a bit of his bumbling that makes me reach the edge of that place where I want to shout "Oh, just kiss her already!" With their budding romance at the end, and their flying off into the moonrise in a zeppelin chased by the Jabberwocky, it seems as if there will certainly be a third book in this graphic novel series.

As a follow-up to Rapunzel's Revenge this book does a nice job filling Jack's past while bringing both characters forward in a continuation of their adventures together. It does occasionally suffer the problem inherent in many comics of bringing readers up to speed with a sort of "origins story" but with some minor reservations the sequel is as strong as its predecessor.

And on a side note, while a certain series concerning Hunger and Games has been anxiously awaited in this house by a certain teen, this was the book my tween daughter could not wait for me to put into her hands at the beginning of summer vacation. She could not (or would not) explain why she wanted to read it so badly, only that she was willing to even clean her room and do her own laundry in order to read it. For what it's worth.

Labels:

'10,

bloomsbury,

dean hale,

fairy tales,

graphic novel,

nathan hale,

shannon hale

Wednesday, August 11

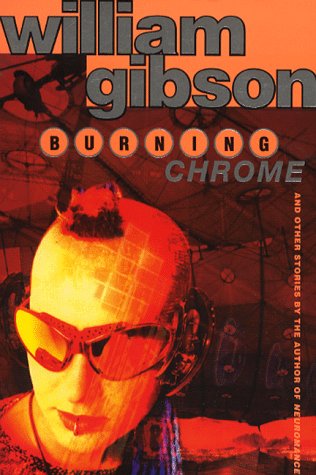

Burning Chrome

and other stories

by William Gibson

various editions since 1986

A classic collection of sci-fi stories by the writer who invented the term cyberspace and probably did more to shape what our vision of the future looks like in movies than most people realize.

Though technically not a book written for children, I am including it here because I think it's a solid read for teens, and have a review for it up at Guys Lit Wire specifically for that purpose. I thought rather than cross posting reviews I'd take this moment to talk a little more about the problem of sci-fi in children's writing. Specifically to ask why there isn't more of it.

As genres go, there are plenty of detective mysteries in children's literature, and books about interpersonal relations between boys and girls to qualify as romance, and certainly enough fantasy to fit any young reader's interest in things from wizards to mermaids to magic. But where are the stories that speak of the future, a future that isn't entirely a dystopic nightmare? Where are the stories that look at the problems of artificial intelligence, that propose difficult solutions to our current problems, allegories and cautionary tales, stories about ideas kids can latch onto?

I think we sell younger readers short by not providing them with these stories and having to send them to the adult shelves to find what they're looking for.

And they are looking for them. If books like The City of Ember and life as we knew it and The Hunger Games and The Adoration of Jenna Fox and Unwound have taught us anything it's that kids really like talking about the issues these books bring up. And this is what science fiction does well, it brings up social issues in settings that allow the reader to perhaps see them for the first time and challenge the thinks they think they know or feel.

Perhaps the fear in providing younger readers with science fiction is that they will take the wrong lessons from it, misinterpret the message in a way that binds and blinds. It was only recently that Ray Bradbury acknowledged that for years people have taken the wrong messages from Fahrenheit 451, that it's not (as its taught in high schools) about censorship, or a reaction to the McCarthyism of the 1950s, but a cautionary tale about the dangers of television destroying the interest in reading. But even as we misread Bradbury's intent the fact remains that the literature provides a point of contemplation, so I'm not sure the excuse holds up as a reason for a dearth of science fiction for children.

Is the problem Science-based fiction?

Have we become a society that fears to discuss speculative ideas based on science and technology for fear of an anti-science backlash? Has science fiction become the Dalits of children's literature, or been smeared with the taint of the creationist-evolutionist battles? My hope is that we can hold back on the aliens, on the life-in-space stories, on all the external elements that get shoved into science fiction for kids, and instead seek out more stories about who we are as a species and where we are headed, or might be headed, down the road.

by William Gibson

various editions since 1986

A classic collection of sci-fi stories by the writer who invented the term cyberspace and probably did more to shape what our vision of the future looks like in movies than most people realize.

Though technically not a book written for children, I am including it here because I think it's a solid read for teens, and have a review for it up at Guys Lit Wire specifically for that purpose. I thought rather than cross posting reviews I'd take this moment to talk a little more about the problem of sci-fi in children's writing. Specifically to ask why there isn't more of it.

As genres go, there are plenty of detective mysteries in children's literature, and books about interpersonal relations between boys and girls to qualify as romance, and certainly enough fantasy to fit any young reader's interest in things from wizards to mermaids to magic. But where are the stories that speak of the future, a future that isn't entirely a dystopic nightmare? Where are the stories that look at the problems of artificial intelligence, that propose difficult solutions to our current problems, allegories and cautionary tales, stories about ideas kids can latch onto?

I think we sell younger readers short by not providing them with these stories and having to send them to the adult shelves to find what they're looking for.

And they are looking for them. If books like The City of Ember and life as we knew it and The Hunger Games and The Adoration of Jenna Fox and Unwound have taught us anything it's that kids really like talking about the issues these books bring up. And this is what science fiction does well, it brings up social issues in settings that allow the reader to perhaps see them for the first time and challenge the thinks they think they know or feel.

Perhaps the fear in providing younger readers with science fiction is that they will take the wrong lessons from it, misinterpret the message in a way that binds and blinds. It was only recently that Ray Bradbury acknowledged that for years people have taken the wrong messages from Fahrenheit 451, that it's not (as its taught in high schools) about censorship, or a reaction to the McCarthyism of the 1950s, but a cautionary tale about the dangers of television destroying the interest in reading. But even as we misread Bradbury's intent the fact remains that the literature provides a point of contemplation, so I'm not sure the excuse holds up as a reason for a dearth of science fiction for children.

Is the problem Science-based fiction?

Have we become a society that fears to discuss speculative ideas based on science and technology for fear of an anti-science backlash? Has science fiction become the Dalits of children's literature, or been smeared with the taint of the creationist-evolutionist battles? My hope is that we can hold back on the aliens, on the life-in-space stories, on all the external elements that get shoved into science fiction for kids, and instead seek out more stories about who we are as a species and where we are headed, or might be headed, down the road.

Monday, August 9

Old Abe, Eagle Hero

The Civil War's Most Famous Mascot

written by Patrick Young

illustrated by Anne Lee

Traditionally-told biography of a bald eagle who was a wartime mascot, which is sort of odd when you think about it. I thought so at least. But this book has bigger fish to fry, like the fact that it's riddled with inaccuracy.

"Found" in a nest high in a tree (i.e. stolen from its home) a Native American (here called an American Indian) named Chief Sky raises a fledgling eagle and then trades it to a farmer named McCann who, though he can farm, cannot apparently fight in the war due to his leg so he sends his eagle in his stead. Old Abe rides a standard into battle for Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry's Company C and, though he has a few close scrapes, comes out alive after over a dozen battles. Once home, Old Abe lives out his life as a celebrity, with a two-room apartment in the state capital and tours to the Liberty Bell in 1876 for the Centennial.

All well and good, if it didn't have so many issues that makes the book more fiction than biography.

This is what happens when you do a life-to-near-death style biography and reshape historical events in the process. One of the problems I have with picture book biographies is when information is diluted for its intended audience who in turn come away with the wrong idea about the story. Chief Sky, as a boy and so clearly not the adult depicted here, spent hours scoping out the tree where the eagle's nest was, and had to fend off attacks by the eagle's parents. This is a far cry from the illustration that shows Chief Sky as an adult calmly standing with a baby bird in his hand. The illustration and text are framed in such a way as to have you believe it was an honorable and humane undertaking, more a rescue than a kidnapping, and not the antics of a boy.

Next we have Chief Sky trading away his bird when his tribe goes downriver to conduct business with the white settlers. It would have been just as easy to start the story here, with Chief Sky trading the eagle away without having to whitewash its provenance, and it wouldn't have affected the story at all. To a point. What isn't in the story, but I learned from a very quick Internet search, was that the bird was traded away for a bushel of corn. I think that's the sort of detail a young reader would find interesting, and would make for a good point of discussion; would you trade away your pet for something, and if so, what would you be willing to trade it for?

Then later, unlike the way it's presented in the book, McCann is reported as having made several attempts to sell the adult bird, finally finding a regiment that paid McCann five dollars (or $2.50, depending on which source you use) for their mascot. Nothing about sending the bird to war in his stead, as suggested in this text.

At this point we're barely a fourth of way into the book, and I've grown impatient about trying to sort out what is ans isn't factual, or at least what is presented in a way that a reader doesn't draw the wrong conclusions. For example, at one point a infantryman is shot and Old Abe is described as dragging "his buddy to safety." At most, an adult eagle is going to weigh 15 pounds and can rarely lift or carry anything above its own weight... and you want me to believe a bird dragged a man ten times its weight to safety? A kid reads that, sees that depicted in a book, they aren't going to question it. Why should they? We're giving them a book and telling them it's non-fiction, meaning it really happened. Do we want them to think we're liars?

Best tidbit also not in the story, according to Wikipedia (which, unlike this book, cites references): Old Abe was a female eagle. I don't fault the Wisconsin soldiers for not being able to correctly sex a bird, but at the very least it could be pointed out and the pronoun "she" could be used throughout the text to indicate that, now, we know better. It sells an audience short to say they wouldn't understand that mistake, or that they'd get confused by a masculine name on a female animal. And it continues to perpetrate known falsehoods. We're back to the myth of Washington chopping down the cherry tree again.

I find it odd that an author who is a science and medical writer (or his publisher for that matter) wouldn't think to include a bibliography. There is some backmatter about bald eagles, which is nice, but nothing specifically about Old Abe that might correct some of the inaccuracies in the text. This would be the place to explain how war stories (like eagles dragging men to safety) were sometimes exaggerated by newspapers, or how it's likely that young Abe "danced" when McCann played music because its wings were clipped and it couldn't fly away, or even how Old Abe was actually female. Also implied with in the subtitle – the most famous Civil War mascot – is the idea that there were other mascots of the war between the states. Like that Dadblamed Union Army Cow. Were there others?

I've said this before (and I've written a critical thesis about it for my MFA) I think that when it comes to presenting biographies and other factual materials to younger readers, particularly readers of picture books, those books need to be accurate, thorough, and perhaps even vetted to make sure the information present or implied isn't misleading. We do no favors to children by teaching them about something or someone new to them if what we teach them is wrong.

written by Patrick Young

illustrated by Anne Lee

Traditionally-told biography of a bald eagle who was a wartime mascot, which is sort of odd when you think about it. I thought so at least. But this book has bigger fish to fry, like the fact that it's riddled with inaccuracy.

"Found" in a nest high in a tree (i.e. stolen from its home) a Native American (here called an American Indian) named Chief Sky raises a fledgling eagle and then trades it to a farmer named McCann who, though he can farm, cannot apparently fight in the war due to his leg so he sends his eagle in his stead. Old Abe rides a standard into battle for Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry's Company C and, though he has a few close scrapes, comes out alive after over a dozen battles. Once home, Old Abe lives out his life as a celebrity, with a two-room apartment in the state capital and tours to the Liberty Bell in 1876 for the Centennial.

All well and good, if it didn't have so many issues that makes the book more fiction than biography.

This is what happens when you do a life-to-near-death style biography and reshape historical events in the process. One of the problems I have with picture book biographies is when information is diluted for its intended audience who in turn come away with the wrong idea about the story. Chief Sky, as a boy and so clearly not the adult depicted here, spent hours scoping out the tree where the eagle's nest was, and had to fend off attacks by the eagle's parents. This is a far cry from the illustration that shows Chief Sky as an adult calmly standing with a baby bird in his hand. The illustration and text are framed in such a way as to have you believe it was an honorable and humane undertaking, more a rescue than a kidnapping, and not the antics of a boy.

Next we have Chief Sky trading away his bird when his tribe goes downriver to conduct business with the white settlers. It would have been just as easy to start the story here, with Chief Sky trading the eagle away without having to whitewash its provenance, and it wouldn't have affected the story at all. To a point. What isn't in the story, but I learned from a very quick Internet search, was that the bird was traded away for a bushel of corn. I think that's the sort of detail a young reader would find interesting, and would make for a good point of discussion; would you trade away your pet for something, and if so, what would you be willing to trade it for?

Then later, unlike the way it's presented in the book, McCann is reported as having made several attempts to sell the adult bird, finally finding a regiment that paid McCann five dollars (or $2.50, depending on which source you use) for their mascot. Nothing about sending the bird to war in his stead, as suggested in this text.

At this point we're barely a fourth of way into the book, and I've grown impatient about trying to sort out what is ans isn't factual, or at least what is presented in a way that a reader doesn't draw the wrong conclusions. For example, at one point a infantryman is shot and Old Abe is described as dragging "his buddy to safety." At most, an adult eagle is going to weigh 15 pounds and can rarely lift or carry anything above its own weight... and you want me to believe a bird dragged a man ten times its weight to safety? A kid reads that, sees that depicted in a book, they aren't going to question it. Why should they? We're giving them a book and telling them it's non-fiction, meaning it really happened. Do we want them to think we're liars?

Best tidbit also not in the story, according to Wikipedia (which, unlike this book, cites references): Old Abe was a female eagle. I don't fault the Wisconsin soldiers for not being able to correctly sex a bird, but at the very least it could be pointed out and the pronoun "she" could be used throughout the text to indicate that, now, we know better. It sells an audience short to say they wouldn't understand that mistake, or that they'd get confused by a masculine name on a female animal. And it continues to perpetrate known falsehoods. We're back to the myth of Washington chopping down the cherry tree again.

I find it odd that an author who is a science and medical writer (or his publisher for that matter) wouldn't think to include a bibliography. There is some backmatter about bald eagles, which is nice, but nothing specifically about Old Abe that might correct some of the inaccuracies in the text. This would be the place to explain how war stories (like eagles dragging men to safety) were sometimes exaggerated by newspapers, or how it's likely that young Abe "danced" when McCann played music because its wings were clipped and it couldn't fly away, or even how Old Abe was actually female. Also implied with in the subtitle – the most famous Civil War mascot – is the idea that there were other mascots of the war between the states. Like that Dadblamed Union Army Cow. Were there others?

I've said this before (and I've written a critical thesis about it for my MFA) I think that when it comes to presenting biographies and other factual materials to younger readers, particularly readers of picture books, those books need to be accurate, thorough, and perhaps even vetted to make sure the information present or implied isn't misleading. We do no favors to children by teaching them about something or someone new to them if what we teach them is wrong.

Labels:

10,

anne lee,

bald eagles,

civil war,

kane miller,

native americans,

patrick young

Friday, August 6

Picture This

How Pictures Work

by Molly Bang

Chronicle Books 2000

A short study on graphic composition that's an accessible introduction to the subject for the artistically inclined, and those who just want to understand better how illustrations 'work.'

Picture book illustrator Bang comes to the subject of her book honestly, at the beginning of her introduction. A visiting friend makes a suggestion about her drawings and then realizes "You really don't understand how pictures work, do you?" Undaunted, Bang decides to do as she's always done with her illustration career, to learn by doing, and in the process comes up with a book that explains how to compose pictures.

By showing her trial and error, and by explaining what is and isn't working, Bang gives us a frame-by-frame construction of a scene from Little Red Riding Hood using essentially only two shapes (triangles and rectangles) and four colors (black, white, red, lavender). Along the way she plays with scale, perspective, balance, focal points, tension, emotion, and other elements that go into the design and layout of an illustration.

In teaching herself these things, Bang originally started by experimenting with third graders before moving on to eighth and ninth graders, and then adults. Working with cut paper collage and keeping the shapes simple she makes the exercise accessible to everyone, though she admits that it is best understood by teens and older.

I would consider this a good fundamental text for students who are interested in the arts. Any of the arts, not just drawing or painting. The ability to compose an illustration is no different than composing a shot in photography or designing a stage set for the theater. Animators need to understand how to direct focus, tension, and emotion within a scene, and even creative writers can benefit from understanding the effects of color in setting tone and establishing themes.

Though there are many other books out there that go into far greater detail about how to draw or compose a drawing or illustration, what Bang's book does is make the ideas accessible and encouraging. A good deal of this probably comes from the fact that Bang herself didn't learn these things formally in an art school setting and so comes about it humbly and suscinctly.

Have have few reference books I would consider required for all students entering high school – Strunk and White's The Elements of Style and Hoff's How to Lie With Statistics – but I'm considering adding Bang's Picture This because, like those other books, it deceptively packs a lot of basic information into very little space and provides a solid foundation for further studies.

by Molly Bang

Chronicle Books 2000

A short study on graphic composition that's an accessible introduction to the subject for the artistically inclined, and those who just want to understand better how illustrations 'work.'

Picture book illustrator Bang comes to the subject of her book honestly, at the beginning of her introduction. A visiting friend makes a suggestion about her drawings and then realizes "You really don't understand how pictures work, do you?" Undaunted, Bang decides to do as she's always done with her illustration career, to learn by doing, and in the process comes up with a book that explains how to compose pictures.

By showing her trial and error, and by explaining what is and isn't working, Bang gives us a frame-by-frame construction of a scene from Little Red Riding Hood using essentially only two shapes (triangles and rectangles) and four colors (black, white, red, lavender). Along the way she plays with scale, perspective, balance, focal points, tension, emotion, and other elements that go into the design and layout of an illustration.

In teaching herself these things, Bang originally started by experimenting with third graders before moving on to eighth and ninth graders, and then adults. Working with cut paper collage and keeping the shapes simple she makes the exercise accessible to everyone, though she admits that it is best understood by teens and older.

I would consider this a good fundamental text for students who are interested in the arts. Any of the arts, not just drawing or painting. The ability to compose an illustration is no different than composing a shot in photography or designing a stage set for the theater. Animators need to understand how to direct focus, tension, and emotion within a scene, and even creative writers can benefit from understanding the effects of color in setting tone and establishing themes.

Though there are many other books out there that go into far greater detail about how to draw or compose a drawing or illustration, what Bang's book does is make the ideas accessible and encouraging. A good deal of this probably comes from the fact that Bang herself didn't learn these things formally in an art school setting and so comes about it humbly and suscinctly.

Have have few reference books I would consider required for all students entering high school – Strunk and White's The Elements of Style and Hoff's How to Lie With Statistics – but I'm considering adding Bang's Picture This because, like those other books, it deceptively packs a lot of basic information into very little space and provides a solid foundation for further studies.

Labels:

00,

art,

chronicle,

composition,

design,

illustration,

middle grade,

molly bang,

non-fiction,

reference,

teens

Wednesday, August 4

boom!

(or 70,000 light years)

by Mark Haddon

David Fickling / Random House 2009

A middle grade my-teacher-is-an-alien story from the author of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time. Entertaining, if strangely familiar.

While secretly eavesdropping on their teachers, Jimbo and his friend Charlie discover that two of their teachers are, in fact, aliens from another world on the far reaches of our galaxy. Once the aliens discover that Jimbo and Charlie know their secret, and are coming for them, the boys decide to follow the clues to a remote Scottish locale that serves as an intergalactic transport station. Finding themselves on the planet Plonk, they learn that the aliens are trying to repopulate their planet with humans (specifically sci-fi fans who find the experience cool) but are temperamental to the point of threatening to blow up Earth. Jimbo and Charlie make their escape with the help of Jimbo's obnoxiously punk sister Becky and, returning home, save the day.

What starts off feeling very much like Bruce Coville's My Teacher is an Alien and winds up feeling like an lost scene from Men In Black is, as can be gleaned, a goofy send-up of aliens-among-us-and-kids-save-the-day. It was a breezy read, and one I think most middle schoolers would enjoy, particularly the boys.

That said, I found it curious while reading the introduction (something I don't normally like to do) to hear Haddon make mention of this being a retread of an earlier published book from 1992. Odd, because The Curious Incident was hailed (by the New Yorker, among others) as his big debut when, in fact, he had a handful of book published before that.

Oh. His big ADULT debut. His books for children don't count.

I remember feeling the same about Gregory Maguire's "debut" Wicked, knowing he had scads of books nearby in the children's section. Perhaps we've gotten away from that notion that a children's book author isn't somehow as legitimate until the "break out" into the adult consciousness, but it still chaps me a bit.

All of that aside, Haddon does a have a way with engaging and funny characters – Jimbo's family is like the most offbeat collection of individuals from a British TV sitcom – and creates a Douglas Adams class of aliens, complete with dated disco-era catch-phrases as their primary form of communication.

In updating the original 1992 book – with it's unpronounceable title of Gridzbi Spudvetch! – Haddon claims to have started with modernizing the technology only to have changed every sentence of the original. I like the idea of a successful author being able to revisit an earlier work and make something new out of it. And if I didn't have a million other things to do it could be instructive to track down a copy of the original and do a side-by-side comparison.

By the way, I went with the Italian edition's cover (a) because I like the yellow instead of the orange that the English language editions have and (b) because it's subtitle La strana avventura sur planeta Plonk translates as "The strange adventure to planet Plonk," which I kinda like.

by Mark Haddon

David Fickling / Random House 2009

A middle grade my-teacher-is-an-alien story from the author of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time. Entertaining, if strangely familiar.

While secretly eavesdropping on their teachers, Jimbo and his friend Charlie discover that two of their teachers are, in fact, aliens from another world on the far reaches of our galaxy. Once the aliens discover that Jimbo and Charlie know their secret, and are coming for them, the boys decide to follow the clues to a remote Scottish locale that serves as an intergalactic transport station. Finding themselves on the planet Plonk, they learn that the aliens are trying to repopulate their planet with humans (specifically sci-fi fans who find the experience cool) but are temperamental to the point of threatening to blow up Earth. Jimbo and Charlie make their escape with the help of Jimbo's obnoxiously punk sister Becky and, returning home, save the day.

What starts off feeling very much like Bruce Coville's My Teacher is an Alien and winds up feeling like an lost scene from Men In Black is, as can be gleaned, a goofy send-up of aliens-among-us-and-kids-save-the-day. It was a breezy read, and one I think most middle schoolers would enjoy, particularly the boys.

That said, I found it curious while reading the introduction (something I don't normally like to do) to hear Haddon make mention of this being a retread of an earlier published book from 1992. Odd, because The Curious Incident was hailed (by the New Yorker, among others) as his big debut when, in fact, he had a handful of book published before that.

Oh. His big ADULT debut. His books for children don't count.

I remember feeling the same about Gregory Maguire's "debut" Wicked, knowing he had scads of books nearby in the children's section. Perhaps we've gotten away from that notion that a children's book author isn't somehow as legitimate until the "break out" into the adult consciousness, but it still chaps me a bit.

All of that aside, Haddon does a have a way with engaging and funny characters – Jimbo's family is like the most offbeat collection of individuals from a British TV sitcom – and creates a Douglas Adams class of aliens, complete with dated disco-era catch-phrases as their primary form of communication.

In updating the original 1992 book – with it's unpronounceable title of Gridzbi Spudvetch! – Haddon claims to have started with modernizing the technology only to have changed every sentence of the original. I like the idea of a successful author being able to revisit an earlier work and make something new out of it. And if I didn't have a million other things to do it could be instructive to track down a copy of the original and do a side-by-side comparison.

By the way, I went with the Italian edition's cover (a) because I like the yellow instead of the orange that the English language editions have and (b) because it's subtitle La strana avventura sur planeta Plonk translates as "The strange adventure to planet Plonk," which I kinda like.

Labels:

09,

1992,

aliens,

humor,

mark haddon,

middle grade,

teachers

Monday, August 2

Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Dog Days

by Jeff Kinney

Amulet / Abrams 2009

The fourth book in the Wimpy Kid series continues with the misadventures of Greg Heffley trying to make it through the summer with as little effort and trauma as possible. But if that happened there'd be no book...

After the initial blast of the first Wimpy Kid book, and the subsequent popularity, I sort of let the series go as one of those things that's good for a laugh not not, you know, something I felt obsessive about. Like Charlie Brown and other cartoon creations, once you know who they are as characters you can pretty much guess their travails and it really becomes a question of individual limits. I know one summer way back when I obsessively read every paperback that had the MAD magazine logo on it, followed by every Wizard of Id collection I could nab. It's a kid thing, a summer thing, a perfectly solid way to wile away those dog days of late July and August.

Wimpy Kid Greg Heffley starts off by claiming that summer is nothing more than a three-month long guilt trip because while everyone else is outside he'd rather stay in playing video games. Of course, everything Greg either attempts or is forced to do that takes him away from his game time supports his thinking that he'd be better off indoors and away from everyone. Which, when you think about it, is a fairly stagnant place for a character to be; anti-social, unable to enjoy anything outside of himself, constantly finding nothing but misery about his situation. Even his attempts to do something constructive – start a lawn care company – is driven by his desire to make money to pay off a country club debt and nothing else. Even when I was laying around reading comics I still had days where I schemed to make money and build massive tree forts that were structurally unsound.

Greg Heffley is a bit of a downer.

But that's what makes him work. Kids recognize what a downer he is and laugh at him, not with him, in a way that sometimes borders on mean. I think Kinney comes up with some great situations for mischief and misadventure, where readers can see with devilish glee what unsuspecting Greg is about to get himself into. But after three books it isn't just wearing thin, its beginning to look like Greg might actually be suffering from sort of brain damage. How else do you explain a character who, as the mock definition of insanity goes, keeps beating his head against the wall expecting a different result? Maybe if the kid had something go right once in a while it would make all the other mishaps and screw-ups have more impact.

By now, these books are criticism- and review-proof. Kids read them, and enjoy them, and despite being mislabeled as graphic novels (they aren't) are perfectly fine amusements.

Amulet / Abrams 2009

The fourth book in the Wimpy Kid series continues with the misadventures of Greg Heffley trying to make it through the summer with as little effort and trauma as possible. But if that happened there'd be no book...

After the initial blast of the first Wimpy Kid book, and the subsequent popularity, I sort of let the series go as one of those things that's good for a laugh not not, you know, something I felt obsessive about. Like Charlie Brown and other cartoon creations, once you know who they are as characters you can pretty much guess their travails and it really becomes a question of individual limits. I know one summer way back when I obsessively read every paperback that had the MAD magazine logo on it, followed by every Wizard of Id collection I could nab. It's a kid thing, a summer thing, a perfectly solid way to wile away those dog days of late July and August.

Wimpy Kid Greg Heffley starts off by claiming that summer is nothing more than a three-month long guilt trip because while everyone else is outside he'd rather stay in playing video games. Of course, everything Greg either attempts or is forced to do that takes him away from his game time supports his thinking that he'd be better off indoors and away from everyone. Which, when you think about it, is a fairly stagnant place for a character to be; anti-social, unable to enjoy anything outside of himself, constantly finding nothing but misery about his situation. Even his attempts to do something constructive – start a lawn care company – is driven by his desire to make money to pay off a country club debt and nothing else. Even when I was laying around reading comics I still had days where I schemed to make money and build massive tree forts that were structurally unsound.

Greg Heffley is a bit of a downer.

But that's what makes him work. Kids recognize what a downer he is and laugh at him, not with him, in a way that sometimes borders on mean. I think Kinney comes up with some great situations for mischief and misadventure, where readers can see with devilish glee what unsuspecting Greg is about to get himself into. But after three books it isn't just wearing thin, its beginning to look like Greg might actually be suffering from sort of brain damage. How else do you explain a character who, as the mock definition of insanity goes, keeps beating his head against the wall expecting a different result? Maybe if the kid had something go right once in a while it would make all the other mishaps and screw-ups have more impact.

By now, these books are criticism- and review-proof. Kids read them, and enjoy them, and despite being mislabeled as graphic novels (they aren't) are perfectly fine amusements.

Labels:

09,

jeff kinney,

middle grade,

summer,

wimpy kid

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)