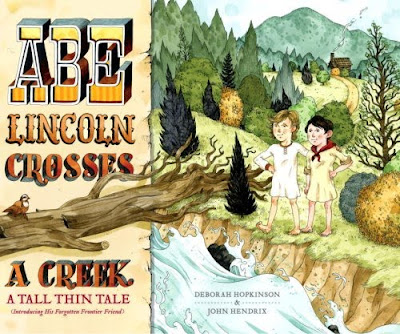

A Tall, Thin Tale

(Introducing His Forgotten Frontier Friend)

by Deborah Hopkinson

picture by John Hendrix

Schwartz & Wade / Random House 2008

If in 2007 a book appeared by a 90 year old author claiming to have been a boyhood friend of JFK, relating an experience where the two as boys nearly drowned in the Charles River of Boston one summer day, where the author saved the young JFK's life and thus played an important role in our nation's history (who would have defeated Nixon in 1960 if JFK weren't even alive?), and there was no one alive who could refute it...

Did it really happen? And would we tell the story as a picture book?

Abe Lincoln Crosses a Creek tells a similar story concerning Abraham Lincoln's Kentucky neighbor Austin Gollaher, about how the the two as young boys attempted to cross a creek, and how Austin rescued Lincoln which allowed him to live and, eventually, become our 16th president. The book attempts to tie up this story with the moral that "what we do matters, even if we don't end up in history books."

That's all well and good, but who's to say it happened? Hopkinson sites at the beginning of the book two titles that quote Gollagher from 1898 and 1921 and a third from 1922 that confirms the story, probably taken from the same sources. Given all the biographical scholarship on Lincoln done in the past 90 years it seems odd that more recent references couldn't be cited.

Unless the story couldn't be proven to modern standards.

Here, again, we see another recent example of the "storyography," the biographical recounting that place story before biography and, in this case, the anecdotal above the known. Hopkinson covers her bases by saying "The events described in this story, so far as this author can determine... did, in fact, take place..." Yes, well, short of Lincoln's personal account, or a third party's account, what we have is, as the subtitle indicates, a tall tale concerning a real individual from history. And since it is a tall tale is there really any reason to lend the story a level of legitimacy by pointing out sources? Does the fact that Lincoln is a character require this level of explanation?

And, as always, shouldn't this information be spelled out to the reader in the text and not placed in tiny type on the Library of Congress page intended for adults who won't be as nearly confused about the legitimacy of the story as the intended reader?

Actually, Hopkinson does attempt to alert the reader in the text that the story contains some questionable details. At the point when Lincoln falls into the creek a giant, incongruous caution warning splashes across the illustration announcing "I want to make sure we get this right. Because maybe it didn't happen like that." The narrative then proceeds with an alternative version of the event in question because, as Hopkinson later suggests, "For that's the thing about history – if you weren't there, you can't know for sure."

Ah, I see. Because we were not there, because the source of the story is perhaps an interested party who could profit from the attention of having been the late president's boyhood friend, because no one can say for sure it didn't happen we can proceed to tell this story as if it did.

A book is a powerful thing. It represents the labors of a lot of people – writers and illustrators, editors and publishers and printers – and when presented by adults like parents, librarians, and teachers takes on the weight of authority in a young reader's eyes. They would not have gone through all this trouble if the story weren't true, would they? When a child is handed Abe Lincoln Crosses a Creek and reads the text only, do they have any reason to doubt the story happened as described, or at all? Do we teach young readers how and when to question historical events and to vet them for accuracy? No, of course not. They accept what they are given because they trust adults to be honest with them.

That said I do not suggest that Abe Lincoln Crosses a Creek should not have been written, and that other books that attempt to tell historical anecdotes from the childhood of historical figures cannot be retold, only that it be clearly and directly related to the reader that such stories might not be factually accurate. There should no question in a reader's mind about the story they have just been told, nor should they confuse that story for history if there is any question.

I have an unusual perspective in this area, having been researching Lincoln's life from the period just after the events in this book. Earlier biographies contain second and third hand accounts of events that do not hold water in biographies written after the 1920s. In fact, I could write a few similar picture books concerning the pre-teen life of Lincoln that, while entertaining, would not be considered accurate by modern Lincoln scholars.

For the past decade we've seen a number of biographical picture books that seem to escape the rigor and expectations we would apply to books intended for older readers. This is a mistake, because (and I think I've said this many times before) that this young age is when we do the most damage in terms of misinformation. Children today STILL have heard the story of Washington chopping down a cherry tree when we now know that the story was a fabrication of Washington's childhood neighbors, told to their children as a morality story, recounted to biographer Parson Weems as gospel truth. It is not true and yet the power of this misinformation still courses through our national psyche.

Accuracy should not suffer at the hands of entertainment, not in the books we present to picture book readers. "What we do matters."

Exactly.

No comments:

Post a Comment