by Jonathan Maberry

Simon & Schuster 2012

Benny and his friends continue on their quest to find what's left of civilization before the zombies and death cults get to them first. Third in a (seemingly) endless series.

Why is it so hard for writers, agents, editors and publishers to know when a story has gone on too long and jumped the shark?

Long-time readers here at the excelsior file might remember how much I loved the first book in this series, Rot & Ruin. In it I thought Maberry had followed the time-honored tradition of using a known genre to explore some aspect of society, to provide a touch of social commentary among the horror. In that particular book I thought he'd touched on an allegory to our own times with zombies acting as a focus of xenophobic fear. There was a sense of "zombies were people, too" that underscored the ignorance of those who would simply choose to fear outsiders and live a life sheltered from the world at large. I thought Rot & Ruin might stand up over time as the beginning of a truly unique series.

The second book, Dust and Decay, was a little more of a hero's journey, the dark passage where Benny would become the merciful zombie silencer all the while working his way through the wilderness on a path toward finding the origins of a jet he once saw, his hope for a rebuilt civilization. In a sort of mash-up of influences there was a bit of a samurai movie that eventually gave way to a Thunderdome-esque ending that threatened to sink the entire story. There was also a hint of a new religion sprouting up from the decay, an apocalyptic death cult that was possibly more organized than Benny and company ever imagined.

Now comes Flesh and Bone, and in the anti-spoiler alert of the year, Benny and his friends don't end up any closer to finding that jet. Perhaps it was something in me that expected the story to come to some conclusion with this third book but it is so clear half way through (and confirmed in the end) that there is a great battle looming in an as-yet-published fourth book that I started feeling bored. How sad, to have felt such great promise in the beginning only to not really care enough by the end of the third book to even want to read the fourth.

I am not against the notion of epic tales, but when I look at a trilogy like Lord of the Rings and see what was accomplished in three books I tend to question whether lengthy series can actually justify their length. I also begin to wonder of the idea of television series, with their seemingly endless storylines, have conditioned readers to amble along until interest drops and then things get hastily wrapped up. Story arcs have multiplied and become so elastic and I don't always think that it serves the best interest of fiction in the end.

So Benny and Nix and Lilah and Chong continue on, with an army of mutated zombies and a war-hungry death cult and escaped zoo animals all venturing into the wastelands of North America. If any traces of civilization survived that civil world has clearly been outnumbered by the rot and decay to the point where this reader asks "What's the point?"

But if your taste runs towards a small band of heroes facing off against zoms, Flesh and Bone's got your number.

Thursday, October 25

Wednesday, October 24

13 Days of Halloween: The Gashlycrumb Tinies

Or, After the Outing

by Edward Gorey

Simon & Schuster 1963

A ghastly little abecedarian for hip little children... who might just happen to be teens or adults with a sense of humor.

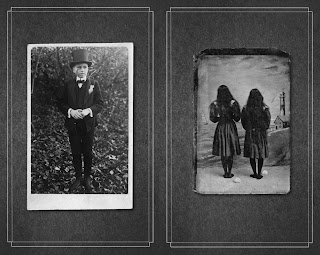

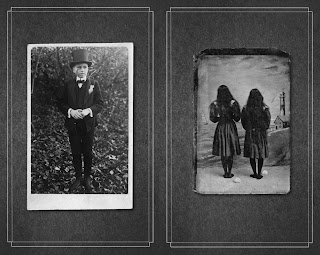

I think this one is best explained by example.

You can probably figure out how the rest of this plays out. Twenty-six children, each with their own half of a dactylic couplet to explain their demise. With his signature illustration style and Victorian sensibilities, Gorey's alphabet poked a sarcastic finger through the overly-protective world of childhood where everything was still see-spot-run and friendly neighbors just down the street and around the corner in classroom readers. It might also be worth noting that the year this was originally published, 1963, was also the same year that brought us Where the Wild Things Are. Change and revolution was in the air and children's books were poised to enter a new era.

It's interesting to think that a book like this would hardly raise a fuss if released today. Picture books are full of subversive humor and tacit violence – ahem, I Want My Hat Back – but Gorey's approach is the reverse of what we see. Where we might have text and image imply some unsavory off-stage happenings Gorey is quite content to lay out precisely what has happened to the poor children and managed to capture them at the moment just before they realized their demise was at hand.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s a high school bedroom or college dorm wall was as likely to have a poster version of The Gashlycrumb Tinies (still very much available, and inexpensive) as it might a Kliban cat, Bo Derek, or A Clockwork Orange poster. Where popular culture continues to march on,leaving some detritus in its wake, I think the resurgence (or recent dominance) of darkness in entertainment makes a Gorey renaissance inevitable. And why not?

by Edward Gorey

Simon & Schuster 1963

A ghastly little abecedarian for hip little children... who might just happen to be teens or adults with a sense of humor.

I think this one is best explained by example.

You can probably figure out how the rest of this plays out. Twenty-six children, each with their own half of a dactylic couplet to explain their demise. With his signature illustration style and Victorian sensibilities, Gorey's alphabet poked a sarcastic finger through the overly-protective world of childhood where everything was still see-spot-run and friendly neighbors just down the street and around the corner in classroom readers. It might also be worth noting that the year this was originally published, 1963, was also the same year that brought us Where the Wild Things Are. Change and revolution was in the air and children's books were poised to enter a new era.

It's interesting to think that a book like this would hardly raise a fuss if released today. Picture books are full of subversive humor and tacit violence – ahem, I Want My Hat Back – but Gorey's approach is the reverse of what we see. Where we might have text and image imply some unsavory off-stage happenings Gorey is quite content to lay out precisely what has happened to the poor children and managed to capture them at the moment just before they realized their demise was at hand.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s a high school bedroom or college dorm wall was as likely to have a poster version of The Gashlycrumb Tinies (still very much available, and inexpensive) as it might a Kliban cat, Bo Derek, or A Clockwork Orange poster. Where popular culture continues to march on,leaving some detritus in its wake, I think the resurgence (or recent dominance) of darkness in entertainment makes a Gorey renaissance inevitable. And why not?

Labels:

60s,

abc,

edward gorey,

picture book,

simon and schuster,

victorian

Tuesday, October 23

13 Days of Halloween: The Monster's Monster

by Patrick McDonnell

Little, Brown 2012

Three little monsters decide to create a much bigger monster who, it turns out, teaches them that you don't HAVE to be a monster, just because you're a monster.

Horned Grouch, hairy Grump, and two-headed Doom 'n' Gloom live in a castle atop a hill where their antics cause the villagers no end of fear. They smash and bash things, get upset over nothing, and their ten favorite words are all 'no.' One day they set out to Frankenstein themselves an ultimate monster but things don't go as plan when Monster turns out to be full of politeness and child-like wonder. Oh, the horror! as Monster teaches them to say Thank You (actually "Dank You" sounding like the late Alex Karras playing Mongo in a Mel Brooks movie), brings them powdered donuts to share, and takes them to the beach to watch the sunrise. Turns out all the little monsters needed was a good role model.

There's something disarmingly cute about this. While thin on character development and motive there seems to be at the core a message about an accepted loss of civility. Or maybe a larger idea about transcending who we think by being shown what we can become. Or maybe it's just a twist on the Frankenstein narrative that suggests our collective "creations" can be larger and better than individual selves.

Or sometimes, a story about monsters is just a story about monsters.

McDonnell's art is breezy and cute in his typical style, though lacking the finer subtleties found in Me, Jane where character expressions on a stuffed animal did as much storytelling as the text. Here, the illustrations are all surface, leaving no real memorable images in their wake as the pages turn. That, coupled with the slight text, makes The Monster's Monster read like a light between-meal snack; more of a rice cracker than a cookie, and essentially calorie-free.

Still, for little monsters who might want a Halloween treat that isn't too scary, this would suffice.

Little, Brown 2012

Three little monsters decide to create a much bigger monster who, it turns out, teaches them that you don't HAVE to be a monster, just because you're a monster.

Horned Grouch, hairy Grump, and two-headed Doom 'n' Gloom live in a castle atop a hill where their antics cause the villagers no end of fear. They smash and bash things, get upset over nothing, and their ten favorite words are all 'no.' One day they set out to Frankenstein themselves an ultimate monster but things don't go as plan when Monster turns out to be full of politeness and child-like wonder. Oh, the horror! as Monster teaches them to say Thank You (actually "Dank You" sounding like the late Alex Karras playing Mongo in a Mel Brooks movie), brings them powdered donuts to share, and takes them to the beach to watch the sunrise. Turns out all the little monsters needed was a good role model.

There's something disarmingly cute about this. While thin on character development and motive there seems to be at the core a message about an accepted loss of civility. Or maybe a larger idea about transcending who we think by being shown what we can become. Or maybe it's just a twist on the Frankenstein narrative that suggests our collective "creations" can be larger and better than individual selves.

Or sometimes, a story about monsters is just a story about monsters.

McDonnell's art is breezy and cute in his typical style, though lacking the finer subtleties found in Me, Jane where character expressions on a stuffed animal did as much storytelling as the text. Here, the illustrations are all surface, leaving no real memorable images in their wake as the pages turn. That, coupled with the slight text, makes The Monster's Monster read like a light between-meal snack; more of a rice cracker than a cookie, and essentially calorie-free.

Still, for little monsters who might want a Halloween treat that isn't too scary, this would suffice.

Labels:

12,

halloween,

little brown,

monsters,

patrick mcdonnell,

picture book

Monday, October 22

13 Days of Halloween: Creepy Carrots

words by Aaron Reynolds

pictures by Peter Brown

Simon & Schuster 2012

Jasper Rabbit loves carrots but they're starting to creep him out. Kids everywhere will cheer - they now have a real reason for hating carrots! They're creepy! But is there a deeper message here about the haves and the have-nots?

Cute Little Jasper loves carrots, and how could he resist the temptation of Crackenhopper Field where they grow fat, crisp, and free? He can't. Then one day his little bunny ears twitch and he is sure he's being followed. Soon enough he is seeing creepy carrots everywhere he looks. The creepy carrots looking at him in the mirror? Those are orange-colored items on the edge of the bathtub. And in the closet? More orange carrot-shaped items.

But after a week Jasper can't help but see those creepy carrots everywhere he looks. Finally Jasper hatches a plan and spends a Saturday enclosing Crackenhopper Field with a fence, surrounded by a moat full of alligators. There was no way any creepy carrot was ever going to escape and haunt Jasper again.

And inside the fence the carrots rejoiced. Their plan had worked!

It's easy to see this as Jasper's story – after all, he's the one being haunted at every turn – but the title of this (literally) dark picture book tells us who the story is really about. These poor, sentient carrots, passive in their existence, have had to deal with the horror of being yanked from the ground and consumed by a bunny with little concern than his own consumption. Is this a story of rabid consumerism? Perhaps, but then would that make the carrots the 99% who haunt in protest for their own rights to exist free of a predatory 1% who think nothing beyond the scope of their own desires.

Reading too much into a picture book again? Maybe the problem is we don't read deep enough.

As haunting as the carrots my be, they are merely creepy as an act of survival, and the ends justify the means as they find themselves in a gated community built on their behalf. That may seem workable for the moment, but how like the social welfare and housing programs of the past where well-intentioned governments (and some ill-intentioned ones as well) construct housing projects and artificial neighborhoods to protect the underclass.

Okay, okay, it's just a story about a rabbit haunted by carrots who are tired of watching kith and kin being eaten before their very carrot eyes. The illustrations in black, grey, and orange deliberately play off the Halloween theme of horror, a little trick-and-treat mixture of cute and creepy. The young'uns will eat it up, but not like carrots. More like candy corn I'd say.

pictures by Peter Brown

Simon & Schuster 2012

Jasper Rabbit loves carrots but they're starting to creep him out. Kids everywhere will cheer - they now have a real reason for hating carrots! They're creepy! But is there a deeper message here about the haves and the have-nots?

Cute Little Jasper loves carrots, and how could he resist the temptation of Crackenhopper Field where they grow fat, crisp, and free? He can't. Then one day his little bunny ears twitch and he is sure he's being followed. Soon enough he is seeing creepy carrots everywhere he looks. The creepy carrots looking at him in the mirror? Those are orange-colored items on the edge of the bathtub. And in the closet? More orange carrot-shaped items.

But after a week Jasper can't help but see those creepy carrots everywhere he looks. Finally Jasper hatches a plan and spends a Saturday enclosing Crackenhopper Field with a fence, surrounded by a moat full of alligators. There was no way any creepy carrot was ever going to escape and haunt Jasper again.

And inside the fence the carrots rejoiced. Their plan had worked!

It's easy to see this as Jasper's story – after all, he's the one being haunted at every turn – but the title of this (literally) dark picture book tells us who the story is really about. These poor, sentient carrots, passive in their existence, have had to deal with the horror of being yanked from the ground and consumed by a bunny with little concern than his own consumption. Is this a story of rabid consumerism? Perhaps, but then would that make the carrots the 99% who haunt in protest for their own rights to exist free of a predatory 1% who think nothing beyond the scope of their own desires.

Reading too much into a picture book again? Maybe the problem is we don't read deep enough.

As haunting as the carrots my be, they are merely creepy as an act of survival, and the ends justify the means as they find themselves in a gated community built on their behalf. That may seem workable for the moment, but how like the social welfare and housing programs of the past where well-intentioned governments (and some ill-intentioned ones as well) construct housing projects and artificial neighborhoods to protect the underclass.

Okay, okay, it's just a story about a rabbit haunted by carrots who are tired of watching kith and kin being eaten before their very carrot eyes. The illustrations in black, grey, and orange deliberately play off the Halloween theme of horror, a little trick-and-treat mixture of cute and creepy. The young'uns will eat it up, but not like carrots. More like candy corn I'd say.

Labels:

12,

aaron reynolds,

bunnies,

carrots,

halloween,

haunting,

peter brown,

picture book,

simon and schuster

Sunday, October 21

13 Days of Halloween: In a Glass Grimmly

by Adam Gidwitz

Dutton 2012

Jack and Jill (and a Frog) went up a beanstalk to fetch a magic mirror. Along the way they outwit Giants, Goblins, a fire-breathing salamander named Eddie, and their parents. A companion to 2010's A Tale Dark and Grimm.

Lately I've been wondering if we do more harm than good by making childhood too safe. I'm not thinking about car seats or non-toxic flame-retardant materials, but a sort of intellectual safety that prevents curiosity and the development of common sense more than it protects. We would prefer to believe it is more important to teach children to fear strangers than to develop an internal sense of knowing when and whom to fear.

The problem (for those who find it a problem) is that without a hard and fast set of rules we have the dual issue of teaching the difficult (intuition) coupled with an unacknowledged root source (adult responsibility, or lack thereof). The sad thing is that there is a solution, its been with us for hundreds of years, and we take it for granted: storytelling. There's a lot that can be learned in a story, and they don't have to be overly moralistic or didactic, and they can occasionally be quite fun. Horrifying, gory, disagreeable and yet unexplainable good fun.

And the best part is that kids really like it.

For those who haven't gleaned it from the title, In A Glass Grimmly, Adam Gidwitz's "companion" to A Tale Dark and Grimm, takes as its source the folk and fairy tales once told to children back when people lived closer to a world full of inexplicable horror. Lacking medicine, much less the concept of hygiene, there were invisible things far scarier than the shadows that dwell in the nearby woods, ah, but what wonderful stories could be constructed from those shadows. As a result, though these tales were as full of the sort of caution we might dole out to our own kids these days it was done with a great deal of adventure, magic, and humorous absurdity as well.

Gidwitz begins with parallel stories about a pair of children, a boy named Jack who is a bit dim and unpopular with other boys, and Jill who is being reared to be as shallow and cruel as her mother. Actually, no, Gidwitz starts with the story of a frog, a hapless amphibian who falls in love with a vain princess, is gifted with ability to speak, and suffers for believing the princess's promises of friendship in exchange for his assistance. These three stories, variants of "The Frog Prince," "The Emperor's New Clothes," and "Jack and the Beanstalk" – all with quite a bit of modification – bind our trio of adventurers out to learn the harsh cruelties the world has to offer in exchange for obtaining the thing each wants most.

The astute reader can find within this tale any frame of reference they bring with them. Even those who might not recognize the original tales Gidwitz creates within his framework will nonetheless recognize the various hero's journeys found in other tales. There's as much Wizard of Oz as there is Lord of the Rings with all the blood and guts and foolishness of the true fairy tales of old. Meant to shock or call attention to the peril, the violence in these stories can be easy to dismiss as "once upon a time" but the cruelty, the psychological terror and abuse adults inflict on these children (and a hapless frog) are still very much real for many readers. If there can be advantage found in stories that reflect contemporary "issues" then I would argue the same for a carefully constructed epic fairy tale like In A Glass Grimmly.

But here's the biggest draw for me: it's fun to read. It's fun and it breezes by, pages flying with unbelievable twists, recognizing old tales and looking for the moments they diverge from their more traditional tellings. Gidwitz likes to break in occasionally (less than in the previous book, which was too bad, because I enjoyed those digressions) and warn the reader of what's to come. There's a wink and a nod because, as much as he's prepared us, the true horrors have nothing to do with the acts of violence about transpire. He's smart enough to trust the reader will know the purpose of these warnings is to break (or increase) tension and playfully knock the reader off balance. It makes the experience interactive, conspiratorial, and, as I said, a kick to read.

Finally, if there is a sense that readers have of "growing out of" fairy tales, as these stories being for more younger children, I'd like to suggest that the real problem comes from a progressive sanitation of these stories over time. It is easy to grow weary of happy endings that come with no larger lesson. The frog isn't turned into a prince by a kiss in the original, he is flung against the wall by the princess in a deliberate attempt to kill him, and when he is revealed to be a prince the princess is so humiliated she spends the rest of her days in his servitude. I daresay things for Frog are much worse here, though in the end he ends up the hero in a way he never was in any fairy tale previously written. If a teen guy were to give this book a chance they might find that they really do still like fairy tales.

(This review originally appeared over at Guys Lit Wire on October 10, 2012)

Dutton 2012

Jack and Jill (and a Frog) went up a beanstalk to fetch a magic mirror. Along the way they outwit Giants, Goblins, a fire-breathing salamander named Eddie, and their parents. A companion to 2010's A Tale Dark and Grimm.

Lately I've been wondering if we do more harm than good by making childhood too safe. I'm not thinking about car seats or non-toxic flame-retardant materials, but a sort of intellectual safety that prevents curiosity and the development of common sense more than it protects. We would prefer to believe it is more important to teach children to fear strangers than to develop an internal sense of knowing when and whom to fear.

The problem (for those who find it a problem) is that without a hard and fast set of rules we have the dual issue of teaching the difficult (intuition) coupled with an unacknowledged root source (adult responsibility, or lack thereof). The sad thing is that there is a solution, its been with us for hundreds of years, and we take it for granted: storytelling. There's a lot that can be learned in a story, and they don't have to be overly moralistic or didactic, and they can occasionally be quite fun. Horrifying, gory, disagreeable and yet unexplainable good fun.

And the best part is that kids really like it.

For those who haven't gleaned it from the title, In A Glass Grimmly, Adam Gidwitz's "companion" to A Tale Dark and Grimm, takes as its source the folk and fairy tales once told to children back when people lived closer to a world full of inexplicable horror. Lacking medicine, much less the concept of hygiene, there were invisible things far scarier than the shadows that dwell in the nearby woods, ah, but what wonderful stories could be constructed from those shadows. As a result, though these tales were as full of the sort of caution we might dole out to our own kids these days it was done with a great deal of adventure, magic, and humorous absurdity as well.

Gidwitz begins with parallel stories about a pair of children, a boy named Jack who is a bit dim and unpopular with other boys, and Jill who is being reared to be as shallow and cruel as her mother. Actually, no, Gidwitz starts with the story of a frog, a hapless amphibian who falls in love with a vain princess, is gifted with ability to speak, and suffers for believing the princess's promises of friendship in exchange for his assistance. These three stories, variants of "The Frog Prince," "The Emperor's New Clothes," and "Jack and the Beanstalk" – all with quite a bit of modification – bind our trio of adventurers out to learn the harsh cruelties the world has to offer in exchange for obtaining the thing each wants most.

The astute reader can find within this tale any frame of reference they bring with them. Even those who might not recognize the original tales Gidwitz creates within his framework will nonetheless recognize the various hero's journeys found in other tales. There's as much Wizard of Oz as there is Lord of the Rings with all the blood and guts and foolishness of the true fairy tales of old. Meant to shock or call attention to the peril, the violence in these stories can be easy to dismiss as "once upon a time" but the cruelty, the psychological terror and abuse adults inflict on these children (and a hapless frog) are still very much real for many readers. If there can be advantage found in stories that reflect contemporary "issues" then I would argue the same for a carefully constructed epic fairy tale like In A Glass Grimmly.

But here's the biggest draw for me: it's fun to read. It's fun and it breezes by, pages flying with unbelievable twists, recognizing old tales and looking for the moments they diverge from their more traditional tellings. Gidwitz likes to break in occasionally (less than in the previous book, which was too bad, because I enjoyed those digressions) and warn the reader of what's to come. There's a wink and a nod because, as much as he's prepared us, the true horrors have nothing to do with the acts of violence about transpire. He's smart enough to trust the reader will know the purpose of these warnings is to break (or increase) tension and playfully knock the reader off balance. It makes the experience interactive, conspiratorial, and, as I said, a kick to read.

Finally, if there is a sense that readers have of "growing out of" fairy tales, as these stories being for more younger children, I'd like to suggest that the real problem comes from a progressive sanitation of these stories over time. It is easy to grow weary of happy endings that come with no larger lesson. The frog isn't turned into a prince by a kiss in the original, he is flung against the wall by the princess in a deliberate attempt to kill him, and when he is revealed to be a prince the princess is so humiliated she spends the rest of her days in his servitude. I daresay things for Frog are much worse here, though in the end he ends up the hero in a way he never was in any fairy tale previously written. If a teen guy were to give this book a chance they might find that they really do still like fairy tales.

(This review originally appeared over at Guys Lit Wire on October 10, 2012)

Labels:

12,

adam gidwitz,

brothers grimm,

dutton,

fairy tales,

gore,

horror,

middle grade,

teen,

YA

Saturday, October 20

13 Days of Halloween: Sailor Twain

by Mark Siegel

First Second Press 2012

A riverboat captain on the 19th century Hudson River nurses an injured mermaid back to health, hidden from his employer who is determined to find and kill her, but is he another of her victims caught in her wrath and fury?

Captain Twain, no relation to Samuel Clemens' alter ego, is a riverboat pilot who runs a tight ship and prefers not to meddle in his passengers affairs. His current employer is the brother of his previous employer who mysteriously became melancholy, disappeared, and was later discovered to have committed suicide. One day Captain Twain discovers a wounded mermaid floating near death in the river. Taking her back to his room he nurses her back to health in secret, bringing her food and telling her stories to entertain her, imploring her not to sing to him so that her song doesn't bind him to her underwater limbo; the Captain's sickly love waits for him and he has no desire to be unfaithful. She agrees, but can she be trusted?

The Captain observes his employer take on many lovers simultaneously, almost methodically, while maintaining a postal correspondence with an author of stories about the supernatural, including mermaids. He also mysteriously throws messages in a bottle into the river and refuses to leave the boat for any reason. It becomes clear over time that his employer doesn't believe his brother committed suicide but has fallen under the spell of the mermaid the Captain is harboring and is, in all his unusual efforts, attempting to undo her power over the souls she has taken.

The Captain observes his employer take on many lovers simultaneously, almost methodically, while maintaining a postal correspondence with an author of stories about the supernatural, including mermaids. He also mysteriously throws messages in a bottle into the river and refuses to leave the boat for any reason. It becomes clear over time that his employer doesn't believe his brother committed suicide but has fallen under the spell of the mermaid the Captain is harboring and is, in all his unusual efforts, attempting to undo her power over the souls she has taken.

Throughout there is the story of the mysterious author who seems to know something about the mermaid of the Hudson, known simply as South, and about the ways she can be defeated. Being a mysterious recluse the author agrees to appear in public and give a lecture on the boat at his employer's invitation. When it turns out the author is a woman the press suggests she's a fraud and even her publishers admit they wouldn't have given her the time of day if they knew or believed their beloved author was a woman. She takes the moment of her heightened publicity to speak out against slavery and women's suffrage and, for a moment, looks to become the last of his employer's lovers which would break the spell the mermaid has over his brother.

Healed, South returns home, inviting Twain to join her below as she believes he is the one she has been waiting for, the one who can release her from the spell that keeps her forever bound to the Hudson river. Torn between wanting to free her and fearing she might take him as she has taken other souls, Twain devises a plan to return his former employer to the world of the living but in the end suffers a fate very similar many who crossed the mermaid of the Hudson.

Initially daunting at 400 pages, Siegel has crafted a haunting tale that tweaks Greek mythology, gothic horror, and the strange romance of life on a river. While Twain's motives aren't always clear, his thoughts not always articulated, he is strangely compelling in the way that he observes and studies those around him in order to piece together what is going on. Granted, much of Twain's movements are for the benefit of the reader, but its only under close critical scrutiny after the fact that a reader might find the otherwise hidden seams holding the narrative together. In truth, the tale was so compelling I was more interested in getting to the end to find out what happened (and giving up precious sleep in the process) that the only time I felt pulled away from the story was in the very active climax where I found things to get a bit muddled.

Indeed, this muddle was further confirmed in the comments section of a review at Guys Lit Wire. Why did the wheelman of the ship sabotage it? Was everyone on board the boat under the thrall of the Mermaid's song? Did Twain himself, like Ishmael, survive to tell the tale only long enough to be reunited with his spiritual self?

Indeed, this muddle was further confirmed in the comments section of a review at Guys Lit Wire. Why did the wheelman of the ship sabotage it? Was everyone on board the boat under the thrall of the Mermaid's song? Did Twain himself, like Ishmael, survive to tell the tale only long enough to be reunited with his spiritual self?

By the end, with the story framed by a his employer's wife who holds the key to Twain's resolution, all I wanted to do was go back to beginning and start all over. I did not want to spend more time with these characters in further tales – or prequels, or backstory – I wanted them to relive their lives in the hope they would make different decisions. It's been a long time I've read a story that made me feel that.

This graphic novel is clearly for the older YA set due to mature sexual themes – almost unavoidable, really, if you want to tell a believable story concerning mermaids. Haunting, brooding, and inevitably people are going to call it the love child of Twain and Poe with, perhaps, a bit of Washington Irving thrown in for good measure.

I'd shortlist this for a Cybil award as well, though with its messy resolution I'd be surprised to see it pass the first round.

First Second Press 2012

A riverboat captain on the 19th century Hudson River nurses an injured mermaid back to health, hidden from his employer who is determined to find and kill her, but is he another of her victims caught in her wrath and fury?

Captain Twain, no relation to Samuel Clemens' alter ego, is a riverboat pilot who runs a tight ship and prefers not to meddle in his passengers affairs. His current employer is the brother of his previous employer who mysteriously became melancholy, disappeared, and was later discovered to have committed suicide. One day Captain Twain discovers a wounded mermaid floating near death in the river. Taking her back to his room he nurses her back to health in secret, bringing her food and telling her stories to entertain her, imploring her not to sing to him so that her song doesn't bind him to her underwater limbo; the Captain's sickly love waits for him and he has no desire to be unfaithful. She agrees, but can she be trusted?

The Captain observes his employer take on many lovers simultaneously, almost methodically, while maintaining a postal correspondence with an author of stories about the supernatural, including mermaids. He also mysteriously throws messages in a bottle into the river and refuses to leave the boat for any reason. It becomes clear over time that his employer doesn't believe his brother committed suicide but has fallen under the spell of the mermaid the Captain is harboring and is, in all his unusual efforts, attempting to undo her power over the souls she has taken.

The Captain observes his employer take on many lovers simultaneously, almost methodically, while maintaining a postal correspondence with an author of stories about the supernatural, including mermaids. He also mysteriously throws messages in a bottle into the river and refuses to leave the boat for any reason. It becomes clear over time that his employer doesn't believe his brother committed suicide but has fallen under the spell of the mermaid the Captain is harboring and is, in all his unusual efforts, attempting to undo her power over the souls she has taken.Throughout there is the story of the mysterious author who seems to know something about the mermaid of the Hudson, known simply as South, and about the ways she can be defeated. Being a mysterious recluse the author agrees to appear in public and give a lecture on the boat at his employer's invitation. When it turns out the author is a woman the press suggests she's a fraud and even her publishers admit they wouldn't have given her the time of day if they knew or believed their beloved author was a woman. She takes the moment of her heightened publicity to speak out against slavery and women's suffrage and, for a moment, looks to become the last of his employer's lovers which would break the spell the mermaid has over his brother.

Healed, South returns home, inviting Twain to join her below as she believes he is the one she has been waiting for, the one who can release her from the spell that keeps her forever bound to the Hudson river. Torn between wanting to free her and fearing she might take him as she has taken other souls, Twain devises a plan to return his former employer to the world of the living but in the end suffers a fate very similar many who crossed the mermaid of the Hudson.

Initially daunting at 400 pages, Siegel has crafted a haunting tale that tweaks Greek mythology, gothic horror, and the strange romance of life on a river. While Twain's motives aren't always clear, his thoughts not always articulated, he is strangely compelling in the way that he observes and studies those around him in order to piece together what is going on. Granted, much of Twain's movements are for the benefit of the reader, but its only under close critical scrutiny after the fact that a reader might find the otherwise hidden seams holding the narrative together. In truth, the tale was so compelling I was more interested in getting to the end to find out what happened (and giving up precious sleep in the process) that the only time I felt pulled away from the story was in the very active climax where I found things to get a bit muddled.

Indeed, this muddle was further confirmed in the comments section of a review at Guys Lit Wire. Why did the wheelman of the ship sabotage it? Was everyone on board the boat under the thrall of the Mermaid's song? Did Twain himself, like Ishmael, survive to tell the tale only long enough to be reunited with his spiritual self?

Indeed, this muddle was further confirmed in the comments section of a review at Guys Lit Wire. Why did the wheelman of the ship sabotage it? Was everyone on board the boat under the thrall of the Mermaid's song? Did Twain himself, like Ishmael, survive to tell the tale only long enough to be reunited with his spiritual self?By the end, with the story framed by a his employer's wife who holds the key to Twain's resolution, all I wanted to do was go back to beginning and start all over. I did not want to spend more time with these characters in further tales – or prequels, or backstory – I wanted them to relive their lives in the hope they would make different decisions. It's been a long time I've read a story that made me feel that.

This graphic novel is clearly for the older YA set due to mature sexual themes – almost unavoidable, really, if you want to tell a believable story concerning mermaids. Haunting, brooding, and inevitably people are going to call it the love child of Twain and Poe with, perhaps, a bit of Washington Irving thrown in for good measure.

I'd shortlist this for a Cybil award as well, though with its messy resolution I'd be surprised to see it pass the first round.

Labels:

12,

boats,

first second,

graphic novel,

legends,

mark siegel,

mermaids,

new york,

river

Friday, October 19

13 Days of Halloween: Zombie in Love

Zombie in Love

by Kelly DiPucchio

illustrated by Scott Campbell

Atheneum Books 2011

A picture book about a zombie looking for love?

Mortimer is, to be blunt, a bit clueless. He's looking for love in all the wrong places, scaring the pants off too many faces. Does he not realize he's a zombie? Does he not understand that the living fear the living dead? In the end, it takes a personal ad (talk about a dead end) to bring Mortimer the one girl who cab return his putrefied affections. At a prom.

Granted, it's got cute moments, but its one of those picture books that make me wonder who the audience is: goth teens looking for a cute Valentine's Day gift? Tweens caught between being too old to trick-or-treat but still clinging to their younger days with newly jaundiced perspectives? Elementary school kids who are already fretting about finding a date for the prom?

The story feels too sophisticated for newly independent readers, full of too much mushy love stuff or too much gore-filled humor, and honestly just seems out of place among other picture books. It's like a zombie-themed valentine on steroids.

I have to say, I was pleased to see a cheerful zombie picture book, but I wished it had been about something other than finding a mate. That's Frankenstein's territory.

by Kelly DiPucchio

illustrated by Scott Campbell

Atheneum Books 2011

A picture book about a zombie looking for love?

Mortimer is, to be blunt, a bit clueless. He's looking for love in all the wrong places, scaring the pants off too many faces. Does he not realize he's a zombie? Does he not understand that the living fear the living dead? In the end, it takes a personal ad (talk about a dead end) to bring Mortimer the one girl who cab return his putrefied affections. At a prom.

Granted, it's got cute moments, but its one of those picture books that make me wonder who the audience is: goth teens looking for a cute Valentine's Day gift? Tweens caught between being too old to trick-or-treat but still clinging to their younger days with newly jaundiced perspectives? Elementary school kids who are already fretting about finding a date for the prom?

The story feels too sophisticated for newly independent readers, full of too much mushy love stuff or too much gore-filled humor, and honestly just seems out of place among other picture books. It's like a zombie-themed valentine on steroids.

I have to say, I was pleased to see a cheerful zombie picture book, but I wished it had been about something other than finding a mate. That's Frankenstein's territory.

Labels:

11,

halloween,

kelly dipucchio,

love,

picture book,

scott campbell,

zombies

Monday, October 8

Squish #4: Captain Disaster

by Jennifer L. Holm and Matthew Holm

Random House 2012

Squish, an amoeba, and his single-cell friends learn life lessons in a primordial soup that looks a lot like an upper elementary school.

As a kid, one of the things I used to love about going out to a restaurant was that the family-friendly places would have comic books for us to read at the table. They were cheesy, with easy-to-solve puzzles and comic adventures that would loosely incorporate the restaurant's mascot and some lesson in good citizenship into eight or twelve pages, the perfect length between ordering and getting food. It was also the perfect length for delivering a didactic message about sharing or bullying or bike safety or recycling or whatever the topic du jour was at the time.

So when I say that Captain Disaster makes me feel like I'm sitting back in a Bob's Big Boy circa 1971 it isn't with a warm and fuzzy glow of nostalgia but with a certain level of puzzlement. Are kids no longer getting these messages in TV cartoons and in other formats that we need them to be produced as graphic novels for a younger readers? Or, conversely, can we not perhaps ask that graphic novels for younger readers elevate themselves above the level of the Archie comics found at the dentist office?

Why does this book make me feel like a snob all of a sudden?

Squish and his friends Pod, also an amoeba, and Peggy, a paramecium, all try out for the soccer team and very quickly learn they don't have any skills. Squish is made team captain and with very little guidance is expected to "steer the ship" of his team forward. While the Coach (a cycloptic crustacean) keeps hammering home the idea of having fun no one on the team is enjoying the fact that they lose every game. Squish's dad suggests that as captain he should try to help take advantage of his teams skills and so he works out a set of winning plays that turns his team around. The problem is that Squish somehow manages to miss the fact that he is always the one to score and Pod and Peggy want to quit the team over it. Realizing that he's focused on winning over inclusion Squish turns things around and returns to the team having fun despite losing. There's a handful of biology terms thrown in occasionally, not enough to build a curriculum around, with a simple physics experiments at the end and a draw-the character page... all of which brings me right back to those restaurant comics.

Maybe it was the times, and the times they are always a-changin', but it seemed like we got comics like this everywhere we went. At the dentist office, sure, in comics and magazines like Highlights and Boy's Life; No trip to a national park was complete without some comic lesson about forest fires or steering clear of bears; Police and firemen would come to classes to teach us bike safety or the dangers of chemicals or electricity, all with cartoon pamphlets; And there were always fairs with kid-friendly material about recycling or public safety or any number of other civic lessons. I guess what I'm trying to say is, this stuff was everywhere, and it was free, and I'm wondering if we really need more of this stuff, stuff like Squish.

Regular reader know I am a very big advocate of graphic novels for kids, and like anything that includes art there is always a question hanging in the air about how one can discuss something like illustrated stories which many seem to think comes down to a question of personal taste. But as I've said before, the rules for graphic novels and comics for kids are the same as narrative text: are the characters multi-dimensional, is the story emotionally complex, are the secondary characters and plots clearly drawn and equally compelling? Time and again when I come across a graphic novel I find weak, and people question my assessment (usually because they disagree with it), I simply say "If this story had its pictures removed and were told as a traditional story, would you find it of a quality you'd be comfortable calling "good storytelling" for kids?

Quite often the answer is "no," and suddenly the question surrounding the value of graphic novels rears its head again.

Squish is not by far the worst offender in this sense, but when I see glowing testimonials from The New York Times, Kirkus, Publisher's Weekly, and The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Studies I can't help wondering when someone's going to realize the emperor is naked. The problem isn't that these comics shouldn't be made, they simply don't hold up as books that don't deserve the heaps of praise they've received.

You tell me, am I being too hard, or are these graphic "novels" for the younger set filling a need that's no longer being met?

Random House 2012

Squish, an amoeba, and his single-cell friends learn life lessons in a primordial soup that looks a lot like an upper elementary school.

As a kid, one of the things I used to love about going out to a restaurant was that the family-friendly places would have comic books for us to read at the table. They were cheesy, with easy-to-solve puzzles and comic adventures that would loosely incorporate the restaurant's mascot and some lesson in good citizenship into eight or twelve pages, the perfect length between ordering and getting food. It was also the perfect length for delivering a didactic message about sharing or bullying or bike safety or recycling or whatever the topic du jour was at the time.

So when I say that Captain Disaster makes me feel like I'm sitting back in a Bob's Big Boy circa 1971 it isn't with a warm and fuzzy glow of nostalgia but with a certain level of puzzlement. Are kids no longer getting these messages in TV cartoons and in other formats that we need them to be produced as graphic novels for a younger readers? Or, conversely, can we not perhaps ask that graphic novels for younger readers elevate themselves above the level of the Archie comics found at the dentist office?

Why does this book make me feel like a snob all of a sudden?

Squish and his friends Pod, also an amoeba, and Peggy, a paramecium, all try out for the soccer team and very quickly learn they don't have any skills. Squish is made team captain and with very little guidance is expected to "steer the ship" of his team forward. While the Coach (a cycloptic crustacean) keeps hammering home the idea of having fun no one on the team is enjoying the fact that they lose every game. Squish's dad suggests that as captain he should try to help take advantage of his teams skills and so he works out a set of winning plays that turns his team around. The problem is that Squish somehow manages to miss the fact that he is always the one to score and Pod and Peggy want to quit the team over it. Realizing that he's focused on winning over inclusion Squish turns things around and returns to the team having fun despite losing. There's a handful of biology terms thrown in occasionally, not enough to build a curriculum around, with a simple physics experiments at the end and a draw-the character page... all of which brings me right back to those restaurant comics.

Maybe it was the times, and the times they are always a-changin', but it seemed like we got comics like this everywhere we went. At the dentist office, sure, in comics and magazines like Highlights and Boy's Life; No trip to a national park was complete without some comic lesson about forest fires or steering clear of bears; Police and firemen would come to classes to teach us bike safety or the dangers of chemicals or electricity, all with cartoon pamphlets; And there were always fairs with kid-friendly material about recycling or public safety or any number of other civic lessons. I guess what I'm trying to say is, this stuff was everywhere, and it was free, and I'm wondering if we really need more of this stuff, stuff like Squish.

Regular reader know I am a very big advocate of graphic novels for kids, and like anything that includes art there is always a question hanging in the air about how one can discuss something like illustrated stories which many seem to think comes down to a question of personal taste. But as I've said before, the rules for graphic novels and comics for kids are the same as narrative text: are the characters multi-dimensional, is the story emotionally complex, are the secondary characters and plots clearly drawn and equally compelling? Time and again when I come across a graphic novel I find weak, and people question my assessment (usually because they disagree with it), I simply say "If this story had its pictures removed and were told as a traditional story, would you find it of a quality you'd be comfortable calling "good storytelling" for kids?

Quite often the answer is "no," and suddenly the question surrounding the value of graphic novels rears its head again.

Squish is not by far the worst offender in this sense, but when I see glowing testimonials from The New York Times, Kirkus, Publisher's Weekly, and The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Studies I can't help wondering when someone's going to realize the emperor is naked. The problem isn't that these comics shouldn't be made, they simply don't hold up as books that don't deserve the heaps of praise they've received.

You tell me, am I being too hard, or are these graphic "novels" for the younger set filling a need that's no longer being met?

Labels:

12,

didacticism,

graphic novel,

jennifer holm,

matthew holm,

random house,

soccer,

young reader

Tuesday, October 2

A Wrinkle in Time

The Graphic Novel

by Madeleine L'Engle

adaptation by Hope Larson

FSG 2012

The classic middle grade book gets a solid graphic novel treatment by award winning artist Hope Larson.

The weird thing about graphic novel adaptations is that they tend to be much longer than their source material, and they rarely convey all the details and explanations in their retelling. Graphic novels conceived as graphic novels from the beginning work to condense story where adaptations, it seems, look to open up narrative, alternately speeding along the story and slowing it down at the same time. There's a certain elasticity of time and events involved.

Could there be a better-suited book for a graphic novel treatment than A Wrinkle in Time?

Meg is an odd duck, rendered here like your typical unruly tomboyish nerd girl. Impatient and impulsive, she doesn't fit in even among her family; her mother has beauty that she envies, her twin bothers the model of normality, and her baby brother Charles is a precocious clairvoyant mistaken by those around him as a moron. Her father? Mysteriously away, subject of much gossip, though truly gone in a way the local townfolk could never conceive (much less believe) if they knew the truth.

Charles is in contact with some old ladies who live in a house in the woods most consider haunted. Mrs. Whatsit at first seems like a doddering old fool, her companion Mrs. Who speaking often in quotation, and eventually the occasionally unfocused apparition Mrs Which presents, taking the form of a Halloween witch. Together, these tree form a trinity of Star Sisters who serve as prophets, guides, and guardians for the journey about to come. A classmate of Meg's, the sensitive outsider Calvin who is better at passing as normal, finds himself drawn to the haunted house in the woods and once united with Charles and Meg they are informed that they can help bring Meg and Charles's father but that the mission involves some peril.

Traveling the wrinkles in time, the sextet make it across the galaxy to the planet Camazotz where a cloud of evil is holding the kid's father as a prisoner. This evil has grown and crept across the galaxy, threatening to force the inhabitants of other planets to succumb to fear and remain orderly and obedient. This evil is controlled by IT, rendered as little more than a massive brain sitting on a pedestal in a protected tower. Utilizing their wits and few tools left them by the Star Sisters they rescue Meg's father but at the expense of losing Charles in the process. They regroup at a safe distance and discuss options for rescuing Charles, where Meg finally comes to realize that this is her destiny, and enters a final confrontation with IT using as her weapon the one thing IT wants but IT doesn't have.

I'm going to admit right here that I am as old as this book, and that I read it when it was less than a decade old. I have vague memories of images from that initial reading that have, over time, merged with images from episodes of The Twilight Zone and The Prisoner, bits and pieces from other science fiction stories (Bradbury and Clarke most likely), and special effect from the occasional badly produced movies that would end up on TV in the afternoons on weekends. Which is to say that the material read fresh to me while at the same time oddly derivative. But more startling to me was the complete mash-up of Cold War fear, Orwellian dystopia, post-war mythology, and a solid dose of budding New Age religious thinking. None of this is negative or unwelcome, as I was suddenly aware of how tame and safe a lot of middle grade fiction is these days by comparison. Talking time travel as if it were as easy as breathing, quoting classic scholars and thinkers, lumping artists and religious icons together as visionaries who have tried to explain the unexplainable... after a while it was a little like the articulation of thoughts from someone gloriously tripping on LSD. Again, not a bad thing, but odd all the same.

I applaud Larson for taking on a classic that, like movies made from books, will no doubt disappoint those who have set ideas of what the characters look like or how certain elements should be rendered. It's also no small feat to take on the telling of a story that has as its base the notion of time travel without any real explanation for how it is possible. Merely referring to "the tesseract" and giving a basic description of how travel across the fifth dimension could easily lose a reader, but the story is carried along by the strong-willed personality of Meg and her through-line desire of finding and rescuing her father.

I applaud Larson for taking on a classic that, like movies made from books, will no doubt disappoint those who have set ideas of what the characters look like or how certain elements should be rendered. It's also no small feat to take on the telling of a story that has as its base the notion of time travel without any real explanation for how it is possible. Merely referring to "the tesseract" and giving a basic description of how travel across the fifth dimension could easily lose a reader, but the story is carried along by the strong-willed personality of Meg and her through-line desire of finding and rescuing her father.

As excited as I was to get my hands on this I had a little bit of graphic novel adaptation remorse after finishing it – I probably should have reread the original novel first and made a true comparison. But I've thought this over and decided that as much as I'd like to think of graphic novels as gateways to reading in general I sincerely doubt a majority of readers are going to read both: unlike book-to-film interest there is little evidence of a similar graphic-novel-to-book conversion taking place. We can debate and discuss this all we want, but the reality is what it is, when a kid finishes a book they don't generally go hunting down the graphic novel adaptation, and vice versa.

With that thought in mind I am glad there is this second, and perhaps slightly more accessible, graphic novel version of A Wrinkle in Time out there. It provides more opportunities to open up young minds and getting their heads wrapped around the notion of time travel and just what intangible is truly the most powerful weapon in the universe. Besides reading, of course.

by Madeleine L'Engle

adaptation by Hope Larson

FSG 2012

The classic middle grade book gets a solid graphic novel treatment by award winning artist Hope Larson.

The weird thing about graphic novel adaptations is that they tend to be much longer than their source material, and they rarely convey all the details and explanations in their retelling. Graphic novels conceived as graphic novels from the beginning work to condense story where adaptations, it seems, look to open up narrative, alternately speeding along the story and slowing it down at the same time. There's a certain elasticity of time and events involved.

Could there be a better-suited book for a graphic novel treatment than A Wrinkle in Time?

Meg is an odd duck, rendered here like your typical unruly tomboyish nerd girl. Impatient and impulsive, she doesn't fit in even among her family; her mother has beauty that she envies, her twin bothers the model of normality, and her baby brother Charles is a precocious clairvoyant mistaken by those around him as a moron. Her father? Mysteriously away, subject of much gossip, though truly gone in a way the local townfolk could never conceive (much less believe) if they knew the truth.

Charles is in contact with some old ladies who live in a house in the woods most consider haunted. Mrs. Whatsit at first seems like a doddering old fool, her companion Mrs. Who speaking often in quotation, and eventually the occasionally unfocused apparition Mrs Which presents, taking the form of a Halloween witch. Together, these tree form a trinity of Star Sisters who serve as prophets, guides, and guardians for the journey about to come. A classmate of Meg's, the sensitive outsider Calvin who is better at passing as normal, finds himself drawn to the haunted house in the woods and once united with Charles and Meg they are informed that they can help bring Meg and Charles's father but that the mission involves some peril.

|

| as always, click image to enlarge |

I'm going to admit right here that I am as old as this book, and that I read it when it was less than a decade old. I have vague memories of images from that initial reading that have, over time, merged with images from episodes of The Twilight Zone and The Prisoner, bits and pieces from other science fiction stories (Bradbury and Clarke most likely), and special effect from the occasional badly produced movies that would end up on TV in the afternoons on weekends. Which is to say that the material read fresh to me while at the same time oddly derivative. But more startling to me was the complete mash-up of Cold War fear, Orwellian dystopia, post-war mythology, and a solid dose of budding New Age religious thinking. None of this is negative or unwelcome, as I was suddenly aware of how tame and safe a lot of middle grade fiction is these days by comparison. Talking time travel as if it were as easy as breathing, quoting classic scholars and thinkers, lumping artists and religious icons together as visionaries who have tried to explain the unexplainable... after a while it was a little like the articulation of thoughts from someone gloriously tripping on LSD. Again, not a bad thing, but odd all the same.

I applaud Larson for taking on a classic that, like movies made from books, will no doubt disappoint those who have set ideas of what the characters look like or how certain elements should be rendered. It's also no small feat to take on the telling of a story that has as its base the notion of time travel without any real explanation for how it is possible. Merely referring to "the tesseract" and giving a basic description of how travel across the fifth dimension could easily lose a reader, but the story is carried along by the strong-willed personality of Meg and her through-line desire of finding and rescuing her father.

I applaud Larson for taking on a classic that, like movies made from books, will no doubt disappoint those who have set ideas of what the characters look like or how certain elements should be rendered. It's also no small feat to take on the telling of a story that has as its base the notion of time travel without any real explanation for how it is possible. Merely referring to "the tesseract" and giving a basic description of how travel across the fifth dimension could easily lose a reader, but the story is carried along by the strong-willed personality of Meg and her through-line desire of finding and rescuing her father.As excited as I was to get my hands on this I had a little bit of graphic novel adaptation remorse after finishing it – I probably should have reread the original novel first and made a true comparison. But I've thought this over and decided that as much as I'd like to think of graphic novels as gateways to reading in general I sincerely doubt a majority of readers are going to read both: unlike book-to-film interest there is little evidence of a similar graphic-novel-to-book conversion taking place. We can debate and discuss this all we want, but the reality is what it is, when a kid finishes a book they don't generally go hunting down the graphic novel adaptation, and vice versa.

With that thought in mind I am glad there is this second, and perhaps slightly more accessible, graphic novel version of A Wrinkle in Time out there. It provides more opportunities to open up young minds and getting their heads wrapped around the notion of time travel and just what intangible is truly the most powerful weapon in the universe. Besides reading, of course.

Labels:

12,

fsg,

graphic novel,

hope larson,

love,

madeleine lengle,

middle grade,

sci-fi,

time travel

Monday, September 24

Oh, Rats!

The Story of Rats and People

by Albert Marrin

illustrated by C.B. Mordan

Dutton / Penguin 2006

Is there any pet more widely considered vermin? The nonfiction picture book examines the facts and myths surrounding the rodent people love to hate.

Stating with a tale from his own life, Marrin recounts how he was playing in a wood pile as a kid when he first came face-to-face with rats. Out his fear his father offered this wisdom: "Learn about them: you'll feel better."

With that we embark on a journey to learn everything we can about rats. We learn their history and evolution, their ratty ways and how they've interacted with people (and the ways people have interacted with them), we learn how they are pesky and how they are yummy, their eradication and their cause in spreading the plague, and even how they have been used (inadvertently as well as deliberately) in scientific research. It's seemingly very thorough for a book that could serve as a first serious introduction to a child learning about – or how to get over their fear of – rats.

One of the elements that takes the edge off the book is the fact that it is illustrated with woodcut-like illustrations, similar in style to the work of Barry Moser. This one-step removal from actual photographs makes the rats seem less threatening though the detail on their faces and the red spot color on the mostly black-and-white images gives them a bit of realism that may still make some queasy. I would have preferred a little more interplay between images an texts – as opposed to small inset circles and sidebar illustrations – but as presented the images and text are still handsomely laid out and designed.

Occasionally the text felt like it drifted between different aged readers. The chapter on rats and the plague seemed to trade on the reader's knowledge of a higher vocabulary and reading sophistication while other chapters contained text that bordered on condescension. Take

Indeed, Bordeaux is a famous place, but a sentence like that has no meaning without context, and even the description of the wine cellars that follows fails to explain the significance of Bordeaux, the cookbook, and what it being famous has to do with rats. Do the rats know Bordeaux is more famous than other wine regions? Does Bordeaux somehow attract more than the usual amount of rats to its cellars? When contrasted with the chapter on the science of the plague and how the rats transmitted the disease, the text in the cooking chapter and elsewhere wavers between reducing facts to their simplest book report factoids and deeper explanations worthy of a kid deeply interested in the subject.

There are other moments where it feels like information has been simplified or facts generally lumped together for the sake of simplicity. There are, according to this book, only two families of rats, though many types of rats are grouped together on the generic terms "black rats" and "brown rats." Any reader clearly interested in rats would want to know these differences in families, just as they would with subjects like snakes, sharks, bees, and so on.

These points aside, I love this book for not shying away from touchier elements, such as people eating rats and details concerning scientific experimentation. It is reasonably well-rounded and keeps its balance between the earnest, respectful, and gross elements that a subject like rats arouses in readers.

by Albert Marrin

illustrated by C.B. Mordan

Dutton / Penguin 2006

Is there any pet more widely considered vermin? The nonfiction picture book examines the facts and myths surrounding the rodent people love to hate.

Stating with a tale from his own life, Marrin recounts how he was playing in a wood pile as a kid when he first came face-to-face with rats. Out his fear his father offered this wisdom: "Learn about them: you'll feel better."

With that we embark on a journey to learn everything we can about rats. We learn their history and evolution, their ratty ways and how they've interacted with people (and the ways people have interacted with them), we learn how they are pesky and how they are yummy, their eradication and their cause in spreading the plague, and even how they have been used (inadvertently as well as deliberately) in scientific research. It's seemingly very thorough for a book that could serve as a first serious introduction to a child learning about – or how to get over their fear of – rats.

One of the elements that takes the edge off the book is the fact that it is illustrated with woodcut-like illustrations, similar in style to the work of Barry Moser. This one-step removal from actual photographs makes the rats seem less threatening though the detail on their faces and the red spot color on the mostly black-and-white images gives them a bit of realism that may still make some queasy. I would have preferred a little more interplay between images an texts – as opposed to small inset circles and sidebar illustrations – but as presented the images and text are still handsomely laid out and designed.

Occasionally the text felt like it drifted between different aged readers. The chapter on rats and the plague seemed to trade on the reader's knowledge of a higher vocabulary and reading sophistication while other chapters contained text that bordered on condescension. Take

Yersina pestis is a bacillus belonging to the family of bacteria shaped like thin rods. Visible only under a microscope, a single plague bacillus is 1/10,000th of an inch in length.compared with

The famous Larousse cookbook includes one for "Grilled Rat Bordeaux Style. Bordeaux is a famous place.

Indeed, Bordeaux is a famous place, but a sentence like that has no meaning without context, and even the description of the wine cellars that follows fails to explain the significance of Bordeaux, the cookbook, and what it being famous has to do with rats. Do the rats know Bordeaux is more famous than other wine regions? Does Bordeaux somehow attract more than the usual amount of rats to its cellars? When contrasted with the chapter on the science of the plague and how the rats transmitted the disease, the text in the cooking chapter and elsewhere wavers between reducing facts to their simplest book report factoids and deeper explanations worthy of a kid deeply interested in the subject.

There are other moments where it feels like information has been simplified or facts generally lumped together for the sake of simplicity. There are, according to this book, only two families of rats, though many types of rats are grouped together on the generic terms "black rats" and "brown rats." Any reader clearly interested in rats would want to know these differences in families, just as they would with subjects like snakes, sharks, bees, and so on.

These points aside, I love this book for not shying away from touchier elements, such as people eating rats and details concerning scientific experimentation. It is reasonably well-rounded and keeps its balance between the earnest, respectful, and gross elements that a subject like rats arouses in readers.

Labels:

06,

albert marrin,

cb mordan,

dutton,

nonfiction,

picture book,

rats

Saturday, September 22

Drama

by Raina Telgemeier

Scholastic 2012

Romance and friendships are tried and tested during the production of a middle grade play where everything is one giant emotional... drama.

Callie is crushing on Greg, and after he breaks up with his girlfriend Bonnie it looks like she might get a chance at him, but after one sweet kiss it goes south when Bonnie and Greg reunite. Good thing there's the upcoming play production to distract Callie from her short-lived non-romance. Better, the play is a Southern love story and Callie is chock full of enough ideas as part of the stage crew to put Greg quickly out-of-mind.

While posting the announcement for auditions Callie meets brothers Jesse and Justin who have their own interests in the play and in short order they all become close friends. Things start to get messy when Bonnie tries out and gets the lead in the play opposite heartthrob West and they start dating. No, things get messy when Callie starts falling for Jesse who has his own heart set on... West? And after the Spring formal, when Greg realizes he's been a bonehead by letting Callie go will she forgive the way he's treated her in the past and consent to be his new girlfriend?

So much middle school drama!

There's a lot of shifting alliances and subtle game-playing that makes Drama feel natural, warm, and authentic to the middle school experience but at the same time Callie ends right where she started, without a love to call her own, without the one thing she had been wanting all along. Has she grown because of her experiences working on the play? Certainly, and she's perhaps learned a thing or two about the heartbreak of choosing the "wrong" guy more than once. But the story ends with Callie and her extended stage crew friends toasting their triumph and making plans for next year's play. She's come full circle but she's right back where she started and it feels extremely anticlimactic.

I had this same sense after finishing Telgemeier previous graphic novel Smile, this sense of a time captured in amber but frozen in a way that left it life-like and lifeless at the same time. Both books read more like static snapshots in a private photo album rather than narratives full of characters who experience growth. Both books ring true because they are true-to-life, but in the same way that a diary can be a true record of events without a real or strong narrative through line. You can follow all the character's emotional upheavals, see everyone interact, get come closure on all the open issues, and still not feel like anyone's really changed.

Unless I've misunderstood and the one true love of Callie's life is the theatre, in which case the story has a bit of an "and then I woke up" feel to it. But I don't think that's was the intention. The thing is, there are plenty of examples of this kind of backstage mixed-up romance, and they tend to be MGM musicals from the Freed unit back in the 1940s and 50s. The "let's put on a show in the backyard" Andy Hardy movies with Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney are cut from this cloth, as is another Judy Garland vehicle, Summer Stock. But these films knew the audience was there for the singing and dancing and didn't hold out for great character revelations. Perhaps that's what felt missing to me, that the graphic novel with a backstage setting didn't have enough singing or dancing? Yes, that's ridiculous of me, but at the same time it makes sense; at least in the musicals there is a sense of emotion conveyed in the song and dance portions.

Among middle grade graphic novels I think there is a lot of great opportunity for realistic contemporary stories like Drama, but I think I'd prefer the ones aimed at a girl audience not focus on romance. That's just a preference, not a scathing indictment.

How long, I wonder, before a true graphic novel wins a Newbery? Or is that just out of the question?

Scholastic 2012

Romance and friendships are tried and tested during the production of a middle grade play where everything is one giant emotional... drama.

Callie is crushing on Greg, and after he breaks up with his girlfriend Bonnie it looks like she might get a chance at him, but after one sweet kiss it goes south when Bonnie and Greg reunite. Good thing there's the upcoming play production to distract Callie from her short-lived non-romance. Better, the play is a Southern love story and Callie is chock full of enough ideas as part of the stage crew to put Greg quickly out-of-mind.

While posting the announcement for auditions Callie meets brothers Jesse and Justin who have their own interests in the play and in short order they all become close friends. Things start to get messy when Bonnie tries out and gets the lead in the play opposite heartthrob West and they start dating. No, things get messy when Callie starts falling for Jesse who has his own heart set on... West? And after the Spring formal, when Greg realizes he's been a bonehead by letting Callie go will she forgive the way he's treated her in the past and consent to be his new girlfriend?

So much middle school drama!

There's a lot of shifting alliances and subtle game-playing that makes Drama feel natural, warm, and authentic to the middle school experience but at the same time Callie ends right where she started, without a love to call her own, without the one thing she had been wanting all along. Has she grown because of her experiences working on the play? Certainly, and she's perhaps learned a thing or two about the heartbreak of choosing the "wrong" guy more than once. But the story ends with Callie and her extended stage crew friends toasting their triumph and making plans for next year's play. She's come full circle but she's right back where she started and it feels extremely anticlimactic.

I had this same sense after finishing Telgemeier previous graphic novel Smile, this sense of a time captured in amber but frozen in a way that left it life-like and lifeless at the same time. Both books read more like static snapshots in a private photo album rather than narratives full of characters who experience growth. Both books ring true because they are true-to-life, but in the same way that a diary can be a true record of events without a real or strong narrative through line. You can follow all the character's emotional upheavals, see everyone interact, get come closure on all the open issues, and still not feel like anyone's really changed.

Unless I've misunderstood and the one true love of Callie's life is the theatre, in which case the story has a bit of an "and then I woke up" feel to it. But I don't think that's was the intention. The thing is, there are plenty of examples of this kind of backstage mixed-up romance, and they tend to be MGM musicals from the Freed unit back in the 1940s and 50s. The "let's put on a show in the backyard" Andy Hardy movies with Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney are cut from this cloth, as is another Judy Garland vehicle, Summer Stock. But these films knew the audience was there for the singing and dancing and didn't hold out for great character revelations. Perhaps that's what felt missing to me, that the graphic novel with a backstage setting didn't have enough singing or dancing? Yes, that's ridiculous of me, but at the same time it makes sense; at least in the musicals there is a sense of emotion conveyed in the song and dance portions.

Among middle grade graphic novels I think there is a lot of great opportunity for realistic contemporary stories like Drama, but I think I'd prefer the ones aimed at a girl audience not focus on romance. That's just a preference, not a scathing indictment.

How long, I wonder, before a true graphic novel wins a Newbery? Or is that just out of the question?

Labels:

12,

drama,

graphic novel,

middle grade,

middle school,

musicals,

raina telgemeier,

romance,

scholastic,

theatre

Wednesday, September 19

Moby Dick

Chasing the Great White Whale

by Eric Kimmel

illustrated by Andrew Glass